Lens Filters: The Definitive Guide (2024)

Lens filters are a great tool to improve your photography style.

But don't get confused!

This guide is not about filters that you can apply on Instagram... quite the contrary.

This guide is about how you can use different types of lens filters (yes, those pieces of glass that you place in front of the lens) to create a bunch of jaw-dropping images straight on camera.

Tons of fun, great creative potential, less time in post-processing... Lens filters have lots of advantages!

Filters are awesome!

So keep reading...

In this guide you'll find everything you need to become an expert in shooting with all types of lens filters.

Everything!

From the types of lens filters (polarizer, ND, GND, UV etc.) and their applications, including a lot of practical examples to inspire you, how to use the PhotoPills ND filter calculator, and a step-by-step explanation on how to use camera lens filters to create amazing effects.

Are you ready?

The adventure begins.

Welcome to the wonderful world of lens filters!

"Obviously, we all look at things through the filter of our own experience." - Malcolm-Jamal Warner

Get this ebook for free now!

Content

- 15 photos shot with lens filters that will inspire you

- Lens filter types (and the effect they produce)

- What lens filters are essential?

- The best lens filters 2024

- How to use the polarizer filter

- How to find out the actual density of your ND filter with PhotoPills

- How to use an ND filter (or several ones)

- How to use an GND filter (and a reverse GND filter)

- How to stack lens filters (ND, GND and polarizer)

- How to shoot a long exposure stacking several lens filters (ND, GND and polarizer)

- How to move lens filters during the long exposure

- How to shoot a long exposure with a light pollution filter

- How to take photos with an infrared filter

- How to take photos with a solar filter

- 10 lens filter tips to improve your technique

- 12 photographers that master the use of lens filters

- It's your turn!

1.15 photos shot with lens filters that will inspire you

A great photo always starts with a great idea.

Something you have imagined, something that you think it would be possible and that you want to capture with your camera.

It's a very simple creative process but it's very, very powerful.

As PhotoPillers (crazy photographers and PhotoPills users) we usually sum it up in three words:

"Imagine. Plan. Shoot!"

It's our motto, our battle cry.

But don't worry, we still haven't forced any PhotoPiller to tattoo it onto his arm, wearing our t-shirt is enough :D

Jokes aside, when shooting with filters, as with any other type of photography, location is key.

Yes, locations are an inspiration.

But if in addition to a dream location, you add some of these resources to your creative process, success is guaranteed :P

Imagine... Let your imagination fly!

Waterfall (1)

While there's no official record, estimates say there may be as many as 10,000 waterfalls in Iceland. Isn't it amazing?

Foss is the Icelandic word for waterfall, and the names of some of the waterfalls are so incredibly hard to pronounce (and to remember!).

I took this picture during our Iceland expedition. And in order to convey motion and the strength of the water falling down I used a 3-stop ND filter.

Sunrise (2)

In order to photograph this dawn golden hour, I had to wait until it had rained first. The pool you see in the foreground is far from the sea and the only way to see it full is after a heavy rain.

Here I used a CPL filter to polarize the lower part of the frame. I wanted to boost the reflection of the clouds in the water to get a symmetry between the ground and the sky.

Speaking about the sky, I had to trust that it had the right clouds: not too high, not too low, not too dense, not too thin... This is the only way I could get the Sun to heat them up and cast a strong orange tint on them.

So to avoid blowing the highlights and to enhance the orange saturation, I used a 3-stop soft GND filter.

Milky Way (3)

In this picture I wanted to create a connection between the stars and one of those rare buildings that our ancestors left for us to enjoy... and photograph!

The photo shows the Milky Way together with an amazing construction: the Naveta d'es Tudons – a remarkable megalithic chamber tomb that you can find in Menorca (Spain). And this building served as a collective ossuary between 1200 and 750 BC. Isn't it amazing?

In order to capture both in a single frame I used a couple of filters: the Optolong clear sky 77mm filter (to reduce the light pollution) and the Kase Starglow filter (to get brighter stars).

Sunset (4)

I consider myself an extremely lucky person for living where I live, on the beautiful island of Menorca (Spain), where seascapes are unique. The perfect place to take long exposures with my lens filters.

Capturing this inspiring and warm Sunset beach photo was a great pleasure.

To get the shot I used 2 lens filters: a 6-stop ND filter to create a silky water effect and smooth the foam and waves, and a 2-stop reverse GND filter to control the highlights (ie. the Sun) because it was very close to the horizon.

Stars (5)

This hut is, along with the Favàritx lighthouse, my favorite photography subject in Menorca.

I've captured it many times and in many situations: at day, at Sunrise, at Sunset, at night with the Moon, with a comet, with the zodiacal light... Everything you can imagine!

As you can see from the picture above, the results are just spectacular!

Drone (6)

Where would you say this photo was taken? On some island in the Caribbean? In a corner of the Indian Ocean?

No... In Menorca! ;)

On the island we are lucky to have one of the cleanest and most pristine coasts in the Mediterranean.

So during the summer I love to fly my drone and capture the waters of Menorca...

Golden hour (7)

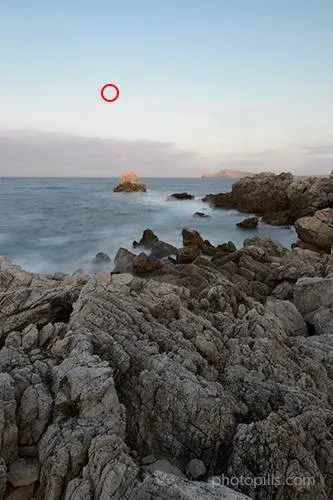

I love photographing the Full Moon during the golden hour: its deep yellow stands out among the roses and oranges in the sky as if it were a fireball.

I wanted to boost the color of the sky, but most specifically, the color of the Moon so I used a soft GND filter. In addition to this, the GND filter helped me avoid blowing out the highlights.

On top of it, I got quite far from the main subject, the Punta Nati lighthouse, so that the Moon looks bigger in the photo...

Blue hour (8)

The Favàritx lighthouse is one of my favorite photographic subjects in the world. Whenever I get a chance, I try to capture it...

It's a perfect location for Sunrises, Moonrises and also for Sunsets and Moonsets.

In this case, I was photographing a Sunrise during the PhotoPills Camp 2019, and the sky was overcast. All of it? Not really.

As you can see in the picture above, there was a narrow strip near the horizon behind the lighthouse without clouds. As the Sun was rising, I decided to take a long exposure with a GND filter to control the highlights in this particular area of the frame.

And since there was little light in the scene I used a small aperture (f/16) to use a slow shutter speed (8s) and create a silky water effect.

Seascape (9)

Imagine a warm, natural glow that makes any landscape look its best. That's the magic of golden hour photography.

In this particular seascape, I wanted to have the Sunset to the side. That way, it would cast an amazing red tone on the side of the rocks in the foreground. I was expecting a sky on fire so I decided to use a GND filter to control the highlights in the sky.

Moreover, I used an ND filter to shoot a long exposure and to add some motion to the water.

Reflection (10)

Whenever I see this picture it brings back great memories of the PhotoPills expedition to Iceland. Those were very emotional days...

But back to lens filters, this photo is a perfect example of how useful a polarizer can be when it comes to highlighting reflections. Especially if you find yourself facing a scene in which the water is perfectly flat.

Once you have the CPL filter mounted, turn it one way or the other while you're composing the photo. You'll see how the water goes magically from being completely transparent to being a perfect mirror.

While you're checking the effect of the circular polarizing filter, change your point of view. As you can see in this photo, the idea was to frame the scene in such a way that the mountains would create a reflection on the water as big as possible. And that's exactly what I did.

Clouds (11)

I love a threatening sky full of clouds. And if there's a storm it's even better. The chances of conveying drama are just amazing.

If you think that the current weather condition prevents you from taking a photo now, it won't be the same in an hour or even ten minutes.

Even though I was 100% sure that I was going to get soaked I was determined to get a shot in this location. There was a relatively strong wind and the clouds were moving from the coastline into the sea. Since I wanted to emphasize the sky I used an ND filter to smooth the water and convey motion through the clouds.

Water (12)

This is a wonderful Sunset that I captured during a lovely winter afternoon. It's a warm scene thanks to the red sky and the reddish tones of the rocks.

I love photographing seascapes. You should know it by now... ;)

So here I used a couple of filters. First, a soft GND filter to avoid blowing out the sky highlights. Then, an ND filter to get a silky effect on the water and enhance the purple tones of the rock in the foreground.

Infrared (13)

Have you been to Iceland?

If you answered "yes", then this location should sound familiar to you.

But if you haven't traveled there, you may have seen this location in the portfolio of one of your favorite landscape photographers. It's an extremely popular place where thousands of photographers go every year.

And I wasn't going to miss the chance... :)

I have to confess that I did take the usual postcard shot that, as I was mentioning before, I'm sure you've already seen online.

But I also wanted to capture a special memory of the Kirkjufell and its waterfalls.

I've had a Nikon with an infrared filter installed on the sensor for many years. And it's a camera that I like to use on special occasions like this one.

If you compare this photo with the regular postcard shot that I took, you'll notice that when I was in Iceland, the Kirkjufell didn't have snow. Neither the rocks and the edges of the waterfalls. Actually, everything had a beautiful green color.

A high contrast black and white image is very similar to any picture you get with an infrared camera. But as I wrote, they're only "similar"...

Well, that's why an infrared filter is magical: it makes you see things that are different from reality ;)

Rainbow (14)

In this scene the greatest challenge wasn't actually the composition, but being able to capture the rainbow formed thanks to the water spray.

Because of the terrain and the location of the waterfall on the Kunene River, the natural border between Namibia and Angola, it was very difficult to work on any composition other than what you see in the photo. I barely had room to position the tripod, but I tried to place it as close as possible to the cliff's edge so that the waterfall would be in the central part of the frame.

But as I told you at the beginning, the key to the image is the rainbow.

To clearly highlight it on the image, I decided to use a polarizer and rotate it until the rainbow stood out as much as possible. Conversely, if I had turned the filter in the other direction, it would have vanished.

Thanks to the ND filter I was able to use a slower shutter speed and thus get silky water to convey strength and dynamism. Those were the same things that I was perceiving while listening to the water fall onto the canyon.

Solar eclipse (15)

Have you ever had the chance to see a partial solar eclipse? And a total one?

No? Well, you should. It's a once in a lifetime experience.

And if you've been as lucky as me, and you've managed to photograph a total eclipse, it's something you'll never forget. Those images will be stuck in your memory (and on your hard drive :)) forever.

Living and photographing the total solar eclipse of August 21, 2017 in Portland (USA) was quite an experience... and a challenge.

I took this photo during the partial eclipse phase, a few minutes before totality, that is the (brief) moment during which the Moon covers the Sun completely.

Obviously, when you're photographing the partial eclipse phase, don't forget to protect your camera with a solar filter and your eyes with a pair of approved eclipse glasses. You'll prevent the sensor and your retinas from ending up severely damaged.

If you also want to learn how to photograph all the phases of a total solar eclipse, including the diamond ring, Baily's beads, the corona, the chromosphere and even details of the Moon's surface, take a look at 'Solar Eclipses: The Definitive Photography Guide'.

The only problem is that a total solar eclipse is not very frequent. So maybe you should start to practice with a lunar eclipse first: 'Lunar Eclipses: The Definitive Photography Guide'.

Photos by PhotoPillers (16) [bonus track]

Throughout this section I have tried to inspire you with examples of photos that you can take using lens filters.

I hope they motivate you to explore your own photography ideas.

But if it's not the case, if you're still a bit lost, I recommend you to check out a very powerful source of inspiration.

Would you like to see lots of photos that other PhotoPillers have imagined, planned and captured all over the world?

What if I told you that not only will you be able to see pictures taken with lens filters, but you will also find pictures of blue hour, golden hour, Sunrise, Sunset, Moon, Milky Way, Star Trails, Meteor Showers, drone, lunar eclipses, solar eclipses and other astronomical events...?

It would be awesome, huh?

Well...

You'll find them in our Instagram account (follow us!) and in the PhotoPills app (My Stuff Menu > Awards).

And if you want us to highlight your photos and inspire other PhotoPillers, you'll find all the information here: PhotoPills Awards.

So... what's next?

Do you feel inspired?

"Sure Toni, now I have a tons of ideas!"

I hope so, because we're about to enter into the exciting world of photography filters.

Let's see the types of lens filters and their practical applications.

It gets bumpy from here on out! :P

2.Lens filter types (and the effect they produce)

Explaining in depth the different types of lens filters and their practical applications is going to take me a while (and a lot of pages)...

The following table is a summary of the options you have.

| Filter | What is it for? |

|---|---|

| Polarizer | Eliminates non-metallic reflections. Eliminates or enhances fog and rainbows. Increases saturation and contrast. |

| Neutral density (ND) | Reduces evenly the light that reaches the sensor. Increases the exposure time. |

| Graduated neutral density (GND) | Gradually reduces the light that reaches the sensor with greater intensity on one of the edges of the filter. Successfully captures scenes with a high dynamic range. |

| Reverse graduated neutral density | Gradually reduces the light that reaches the sensor with greater intensity from the center of the filter. Successfully captures a high dynamic range scenes. |

| Ultaviolet (UV) | Blocks ultraviolet rays. |

| Light pollution reduction | Prevents sodium vapor bulbs from changing the color temperature of the night scene. |

| Solar | Allows to photograph directly the Sun or a solar eclipse preventing the sensor from capturing infrared (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) rays. |

| Black card | Prevents light from reaching the sensor. |

| Infrared | Allows only infrared light to reach the sensor. |

| SharpStar2 | Focusing aid to consistently get sharp, focused stars. |

| Gold-N-Blue Polarizer | Adds variable gold or blue tones to reflections depending on the orientation of the filter. |

| Varicolor Blue/Yellow Polarizer | Adds variable gold or blue tones to reflections depending on the orientation of the filter. |

| Skylight | In film cameras, it offsets the bluish cast that some scenes can have. |

As you can see, the creative options you have with lens filters are endless!

But let's start from the beginning...

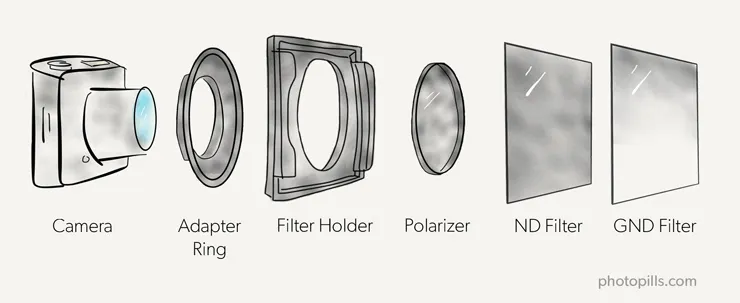

What is a lens filter?

A lens filter is a piece of gear that you place in front of the lens of your camera and allows you to achieve a series of effects (see table above) that otherwise would not be possible (or almost impossible).

The lens filter actually modifies the light and/or color that reaches the camera sensor so you get a correct exposure or achieve a specific effect. Later on, I'll go into depth on these effects as I explain in detail each of the different lens filter types.

A lens filter can be made of

- Glass. It's the best quality material, gives better results and produces fewer side effects, so it's more expensive.

- Resin. It gives a very high quality product both in color accuracy and optical quality.

- Polyester. It's a good, low cost alternative to glass or resin, but it may produce a less perfect effect.

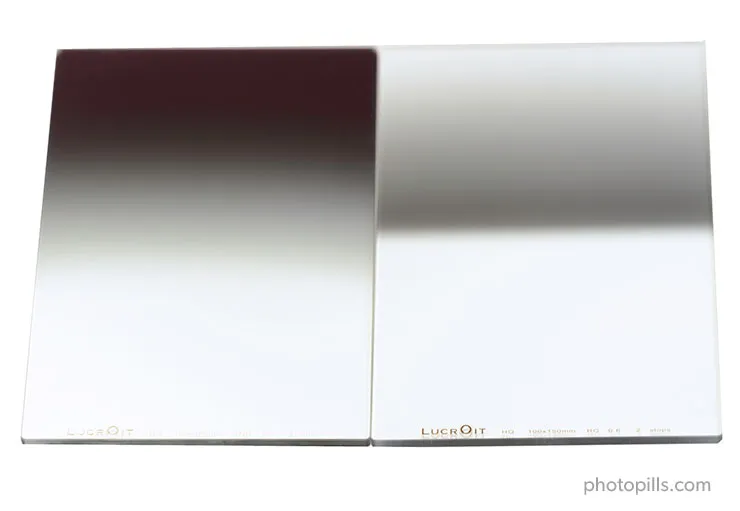

"Toni, what lens filters do you use?"

I use Lucroit glass filters. I like them because, although they are more expensive than those of other brands, they allow me to produce higher quality images. So it's worth spending a bit more money on them.

In section 4 you'll find specific recommendations on what I consider the best lens filters.

Let's keep going.

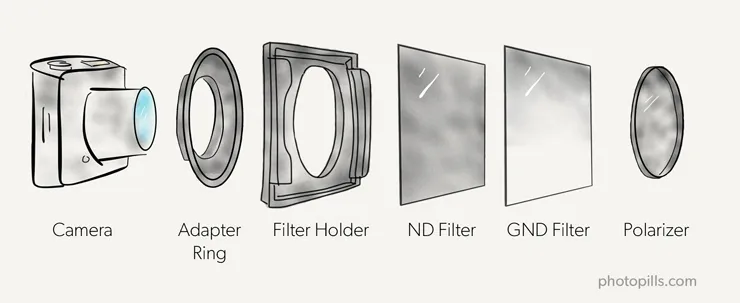

A filter can be circular screw-on, drop-in, square or rectangular.

And depending on its shape, the mounting method onto the lens varies. The mounting method is known as a "system".

Lens filter systems (or mounting methods)

There are several filter systems:

- The square or rectangular (my favorites).

- The circular screw-on.

- The drop-in for some telephoto lenses.

- The square gel lens filter for some wide angle lenses (very rarely used so I won't go into detail).

Square and rectangular lens filters

Certain lens filters can be square (usually neutral density or ND) or rectangular (graduated neutral density or GND ones).

Square lens filters can come in many different sizes (70, 75, 100, 150, 165 and 180mm), although the most common one is 100mm.

Rectangular ones can be 67x85, 75x90, 70x100, 100x150, 150x170, 165x200 and 180x210mm, although the most used size is 100x150mm.

How do you know your square and rectangular lens filter size?

It's very simple.

It depends on the minimum focal length of your lens.

Imagine you have this very popular beginners' lens: the 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 from Nikon (or any other brand).

If you use it with an APS-C camera, take into account the cropping factor (1.5x for Nikon). Thus, the field of view at 18mm will be a bit wide (18 x 1.5 = 27mm). In this case, a 100mm lens filter will be more than enough.

Let's suppose now that you have a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8. It's a very fast and high-end wide angle lens.

If you combine it with a full frame camera and you take a picture at 14mm, the field of view of this lens is so wide that any lens filter smaller than 165mm will create a beautiful vignetting in the corners... XD

If you have a Micro 4/3 camera, that is a camera with a relatively small sensor, be careful with the size of lens filters you use.

Why? Because if you use lens filters that are too big for this system, the transition area may cover a good portion or all of the image. The lens filter will be behaving more like a blender rather than a GND.

Moreover, sometimes you can use a hard GND filter as a soft GND if you have a Micro 4/3 camera.

In fact, if you have doubts about any of your lenses, the best thing to do is read reviews online. Or ask at your local photo store. It's very easy to find reliable information.

Be careful with the GND filter transition

I'll go into detail of all the transitions a GND filter can have later on.

But I just wanted to warn you about one thing...

The focal length, the aperture you set and the sensor size affect your lens filter transition.

Due to the "zoom" effect, the transition in a super telephoto lens (focal lengths above 200mm) looks much softer compared to a wide angle lens (focal lengths below 24mm).

In addition to this, the greater the aperture the more blurred you'll see the gradient, as a result of the shallower depth of field.

Advantages of using square and rectangular lens filters

- You need a filter holder to use them, that is a piece of plastic or metal that you attach to your lens.

- The filter holder has several slots where you can slide several filters at the same time.

- As these lens filters are not circular, nor do they depend on a specific lens size, they are perfectly interchangeable. Therefore, you can use the same filters with different lenses.

- It's easy to slide the GND filters very precisely to position the transition exactly where you need.

- You won't get any vignetting.

Drawbacks of using square and rectangular lens filters

- They are bigger than a circular filter and much more fragile. If you drop one of your lens filters on the ground, it will most likely break.

- You need a filter holder to be able to use them, so you'll need to carry more equipment. The filter holder is not essential, you could hold the filter with your hand depending on the shutter speed, but I highly recommend you to use one because it will make your life easier.

The most popular brands of square and rectangular lens filters are Lucroit, NiSi, Lee, Benro, Formatt-Hitech, Cokin, Singh-Ray, Kase, Breakthrough and Haida.

If you're interested in buying lens filters:

- You can find my suggestions on the must-have lens filters in section 3.

- I tell you everything about the best lens filters in section 4.

Circular screw-on lens filters

A circular filter is a piece of glass, resin or polyester in the shape of a circle that has a metallic edge so you can screw it onto the lens thread.

Some of the common sizes for circular lens filters are 43mm, 49mm, 52mm, 44mm, 58mm, 62mm, 68mm, 72mm, and 77mm.

How do you know your circular lens filter size?

Obviously, the size of the lens filter you should buy depends on your lens' specific diameter.

So, at first sight, you may not be able to use a circular lens filter of a certain diameter on a lens that doesn't have that specific diameter.

And I've written "at first sight" on purpose because you can always get a tool that allows you to use the same circular filter on different lenses – an adapter ring.

Imagine you have a 77mm diameter lens and a 58mm diameter one. My recommendation would be to buy a 77mm circular lens filter and an adapter ring to screw it onto your 58mm lens.

Keep in mind that it doesn't work the other way around. In other words, if you had a 58mm filter, it wouldn't cover the entire surface of your 77mm lens, so you would end up seeing the filter edges in the photo.

Therefore, your circular filter should have the same diameter as your bigger lens.

Advantages of using circular lens filters

- You can leave them screwed onto your lens so mounting them is very simple and fast.

- It's very easy to stack them as you only have to screw one on top of the other.

- They are relatively small and thin so they are easily stored and transported.

- They are more resistant than other types of filters.

Drawbacks of using circular lens filters

- Because they have to fit into the thread of your lens, they must have a specific diameter. So it's complicated to interchange between one lens and another. However, as I explain in section 15 there's a turnaround – using a step-up ring.

- Circular lens filters can be difficult to unscrew. Sometimes they get stuck and are hard to handle in cold and low temperature situations.

- When you want to apply several filters, placing them on top of each other produces vignetting (darkening of image corners when compared to the center).

In my opinion, these reasons are enough to recommend you to use square and rectangular filters. They are the lens filters I use and I love them.

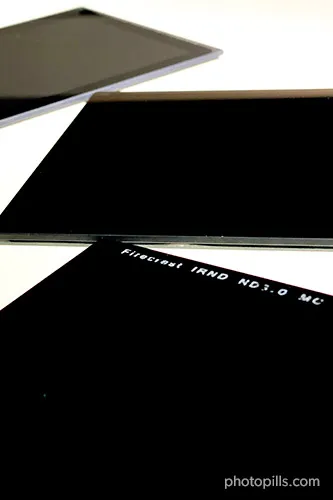

However, that doesn't mean that you can't stack circular filters with square and/or rectangular filters. For example, the B+W ND 3.0 (10 stops) circular filter is spectacular. So you could include it in your kit and, at the same time, use a rectangular GND filter along with a filter holder.

It's not the most comfortable combination in the world, but it can be a very good option depending on the type of filters you have and the quality you're looking for.

If you're interested in buying circular filters, these are the most popular brands: Hoya, B+W, Haida, Tiffen, Breakthrough, Singh-Ray, NiSi, Formatt-Hitech and Haida.

Drop-in lens filters for telephoto lenses

A drop-in lens filter is only used for telephoto lenses with a long (from 200mm) or very long (up to 800mm) focal range.

The problem with any long-range and some angular telephoto lenses is that the front lens is so large that no conventional lens filter, whether circular, square or rectangular, can help you get the effects you're looking for.

Instead, these lenses have a slot in the back where you can insert a drop-in glass lens filter. This slot has nothing to do with another slot that certain wide angles have and where you can insert a very thin pre-cut gelatin sheet. These gelatin sheets also act as a filter, although for other purposes.

As you can see in the photo below, to insert the filter in this slot you need an adapter where you can place a neutral density filter (ND) filter or a polarizer filter.

You'll be using circular filters in both cases, so they must have a specific diameter to fit perfectly into the adapter and then into the telephoto lens.

Now that you know the different mounting systems to attach the filter to the lens of your camera, let's focus on the different types of filters and their applications.

Depending on the effect you want to get in your final image, you'll use one filter or another.

So let's see the different types of filters, their uses, and their advantages and disadvantages.

Polarizer (CPL) filter

What is a polarizer (CPL) filter?

A circular polarizing filter (CPL) is a piece of glass that reduces the amount of reflected light entering through the lens of your camera and captured by the sensor.

When light waves hit a non-metallic surface, they bounce off and are reflected along a parallel plane to that surface.

Depending on how you position the polarizer and how you rotate it, you can block these waves that travel along a specific plane. Therefore, as you rotate the filter, these effects appear or disappear.

Moreover, you can control the intensity of this effect by changing the camera's line of focus with respect to the Sun.

In other words, the circular polarizer filter is perfect for removing reflections, as long as they're non-metallic.

Types of polarizing filters (and how they work)

Polarizing filters can be linear or circular.

But don't get confused!

The name of these filters has nothing to do with their shape (square or round), or the fact that they rotate (every single one does), but with the way they work.

As I said at the beginning of this section, this type of filter depends on the behavior of the light.

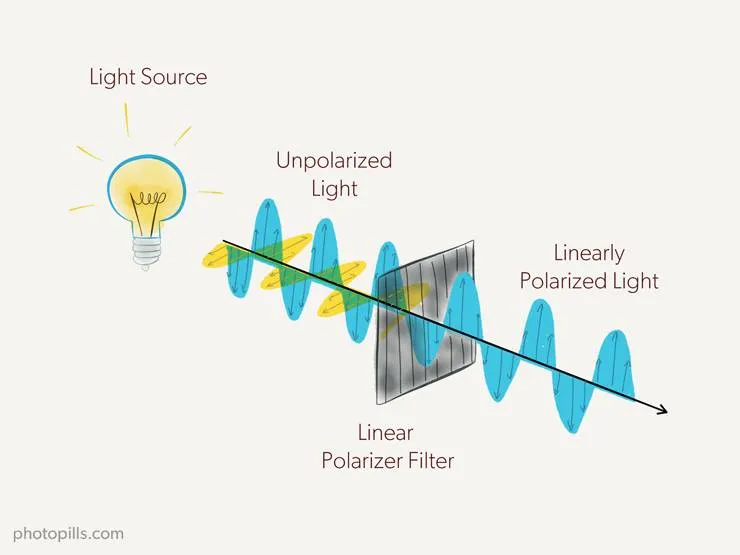

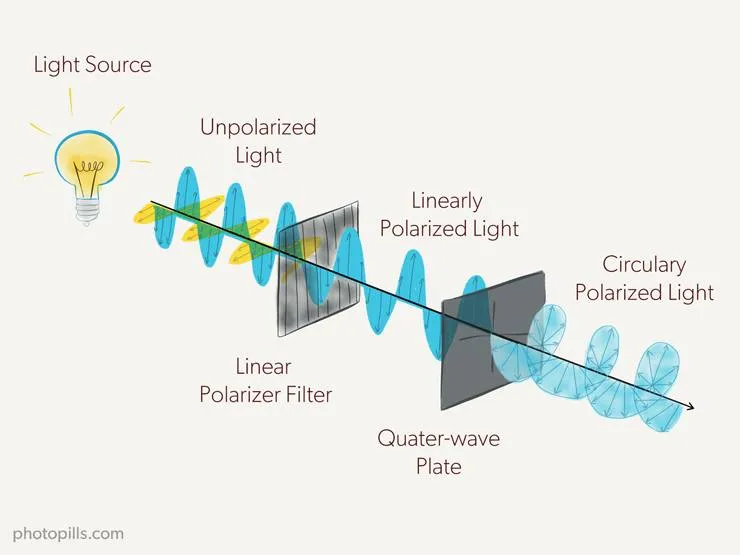

When a beam of light moves in a straight line, it does so as it oscillates in an infinite number of planes around the axis that marks the movement direction. Each of these planes is a polarization plane. So with the polarizer you can reduce all those planes to one or a very small range of them.

Maybe this diagram will help you understand it better.

This is how a linear polarizing filter works.

But there's a problem...

Well, your DSLR or mirrorless camera may not work properly.

Don't panic, it won't break down. The thing is that, as the light is polarized linearly in a single plane, the light meter or the autofocus system can be confused when metering. And your photo will be badly exposed, out of focus or both.

How can you avoid it?

Correct!

Using a circular polarizing filter (CPL). This type of filter has a second element, called a quarter wave plate that converts the already linearly polarized light into a circular polarization, thus avoiding any problems with the light meter or the autofocus system.

Why should you use a polarizing filter?

There are two main reasons:

- It's extremely easy to use.

- It creates an effect that you can't reproduce in post-processing.

As I explained to you before, using a polarizing filter is super easy. All you have to do is rotate the filter. Depending on how darker it is, reflections will disappear.

However, you can't replicate the effect of a CPL filter in post-processing. There's no way to reduce any glare or haze in a scene without a polarizer. That's why I always recommend having one with you when going on a shooting session.

When to use a CPL filter

Again, with a polarizer you can remove:

- Non-metallic reflections. It's very useful for example to make the water more transparent and show more detail on the background.

- Glitter on the surface of an object.

- Part of the mist in the scene.

Remember that is something that you can't achieve with Lightroom or Photoshop.

Another interesting thing that you can get with this filter is to increase the saturation and contrast of your photo.

One of the biggest frustrations we landscape photographers have is that our photos sometimes lack color saturation.

Why?

Well, this is mainly due to the way the light bounces off the ground and all the other elements in the scene. The light bounces following a series of specific angles (each angle depends on the element in which it bounces), so the image looks dull and flat.

However, if you place a circular polarizing filter in front of your lens and rotate it to a certain angle, the filter is able to eliminate most of the light reflected in your scene. In other words, it increases your photo saturation and contrast.

Similarly, when shooting distant subjects (e.g. a mountain range), the polarizer reduces the haze.

Finally, a CPL filter increases the sharpness and the detail quality of your photos.

What are the drawbacks of using a polarizing filter?

Unfortunately, polarizing filters have a number of disadvantages and problems.

Here are some things you should be aware of:

- A polarizing filter can ruin the sky in your shot. If you use a polarizer with a wide angle lens during a Sunrise or Sunset it can make the sky appear unnaturally dark in certain areas. This is also true for panoramas. Be very careful when making panoramas: any problem or effect caused by the polarizer will be almost impossible to correct in post-processing.

- It'll take you longer to compose if you use a polarizing filter because you need to rotate it carefully until you get the effect you're looking for. Don't forget that the polarizing effect of the filter varies greatly depending on the position of the Sun and the direction in which you're pointing the camera.

- A polarizing filter subtracts light from the scene. Depending on the model, it can be between 1 and 3 stops so you need to take this into account when setting the shutter speed.

- A polarizer can cause vignetting. This is especially true if you use a wide angle lens because vignetting will affect the corners of the frame. To avoid this, you shouldn't stack too many filters and only buy slim or nano polarizing filters.

- A polarizer may produce flare or halos in the final image.

- For any polarizer, a rainbow is reflected light. If your polarizing filter is engaged, the rainbow will disappear from your photo. Rotate or remove the polarizer.

- Finally, a quality polarizing filter is expensive. Instead of buying many different sized filters, I recommend that you buy the largest diameter filter you can screw onto your bigger lens. Then, buy adapter rings for all the other lenses you have. That way you can use the same filter with all your lenses.

Despite these drawbacks, I believe that a circular polarizing filter (CPL) is an essential accessory in the backpack of any photographer (especially landscape ones). With a high quality filter and a little practice you can get spectacular results.

And not only that.

Remember you can't replicate the effect of a circular polarizing filter (CPL) using any post-processing software. If you don't get it on camera while in the field, you won't get at home in front of the computer.

Also, as you'll learn in section 9, you can stack the polarizer with other lens filters such as ND or GND ones for spectacular results.

The most popular brands are Lucroit, B+W, Formatt-Hitech, NiSi, Lee, Hoya, Haida, Cokin, Breakthrough and Singh-Ray.

If you're interested in buying lens filters:

- You can find my suggestions on the must-have lens filters in section 3.

- I tell you everything about the best lens filters in section 4.

Neutral density filter (ND)

What is a neutral density (ND) filter?

A neutral density (ND) filter is a piece of glass or semi-transparent resin that you place in front of the lens.

It allows you:

- Increase the exposure time.

- Use a very large aperture (small f number).

The idea in both cases is to get spectacular effects in your photos.

When to use an ND filter?

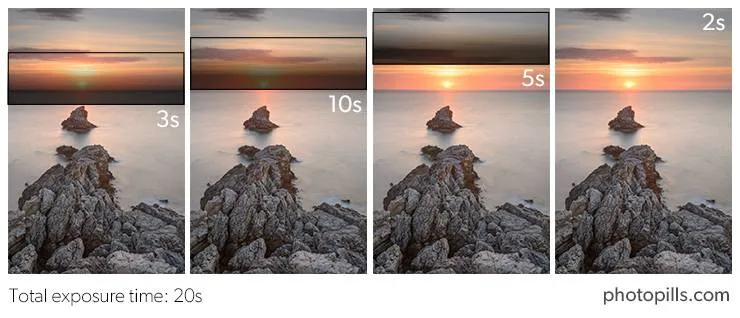

The first picture was taken without an ND filter. In the second one, you can see how the ND filter allowed me to increase the exposure time creating a nice silk effect in the moving water.

In section 7 I explain in depth how to use ND filters. You should definiteIy read this section carefully ;)

Straight to the point...

The ND filter allows you to evenly reduce the light that reaches the sensor. It allows you to subtract light (always evenly, remember). This helps you capture certain effects without overexposing the scene:

- You can slow down the shutter speed to create beautiful effects without overexposing the brightest tones. It allows you, for example, to capture a silk effect in the sea during a Sunset.

- You can use larger apertures (without overexposing the scene) to capture a shallower depth of field. This is useful, for example, if you want to separate the backlit subject from the background.

- The effect you get depends on the number of stops you're able to subtract according to the filter you're using (1, 2, 3 stops...).

Another advantage of the neutral density filter is that since it reduces light evenly, it doesn't alter the contrast or sharpness of your image.

Nor does it introduce any color cast. Or it shouldn't because, unfortunately, it's not always the case depending on the filter manufacturer.

Nevertheless, the density of these filters is "neutral" because of this lack of color cast.

In short, they are sunglasses for your lens.

ND filter chart

With an ND filter you block part of the light entering through the diaphragm to the sensor. And to do that, you need to "subtract" that light precisely. That's why manufacturers offer a wide range of filters of different densities.

In this ND filter table you'll find the most common filters, depending on their density or light reduction capacity.

| Filter | Light reduction (stops) | Density | Light transmission % |

| ND2 | 1 | 0.3 | 50% |

| ND4 | 2 | 0.6 | 25% |

| ND8 | 3 | 0.9 | 12.5% |

| ND16 | 4 | 1.2 | 6.25% |

| ND32 | 5 | 1.5 | 3.125% |

| ND64 | 6 | 1.8 | 1.563% |

| ND128 | 7 | 2.1 | 0.781% |

| ND256 | 8 | 2.4 | 0.391% |

| ND400 | 8 2/3 | 2.6 | 0.25% |

| ND512 | 9 | 2.7 | 0.195% |

| ND1024/ND1000 | 10 | 3.0 | 0.098% |

Thus, an ND 0.3 filter reduces 1 stop the light reaching the sensor. An ND 0.6 filter reduces 2 stops, an ND 0.9 filter reduces 3 stops, an ND 3.0 filter reduces 10 stops, and so on.

Remember, each time you reduce the exposure 1 stop, the sensor captures half the light.

Therefore, a filter allows only 1/(2power) of the initial light to go through it. In this case, "power" is the number of stops that the filter subtracts.

For example, a 6-stop neutral density filter only allows 1/64 of the light to go through your lens:

1/(26) = 1/(2×2×2×2×2×2) = 1/64

Depending on the light you want to subtract, choose a more or less dense filter.

But... Be careful!

The density indicated by the manufacturer is not always the real one, so I suggest you calibrate your ND filters.

If you're interested in buying lens filters:

- You can find my suggestions on the must-have lens filters in section 3.

- I tell you everything about the best lens filters in section 4.

How to calibrate an ND filter?

By "calibrate" I mean "find out the actual density of the ND filter". It's a very simple process that I explain in detail in section 6.

Now, let's get on with the GND filters!

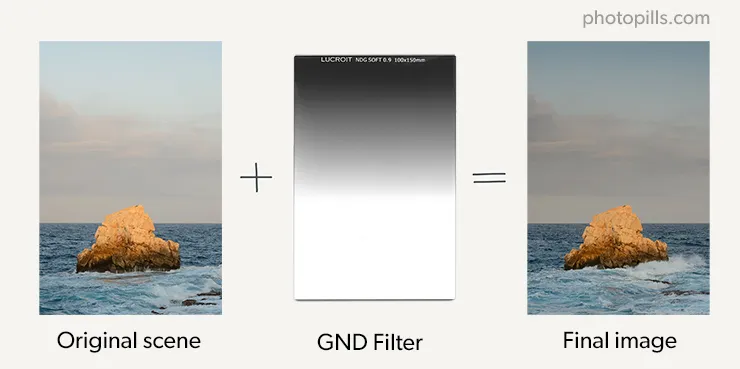

Graduated neutral density filter (GND)

What is a graduated neutral density (GND) filter?

A graduated neutral density filter (GND) is a piece of glass or resin that you can place in front of your lens.

But, unlike ND filters, the density of a GND filter varies gradually on its surface (it isn't uniform). It's made up of two distinct parts: a completely transparent area, and a darker section.

It allows you to:

- Reduce the exposure difference (dynamic range) in the frame. In other words, remove light just in a specific area of the image, like the sky, for instance.

- Increase local contrast. That is, the detail and color of the image are improved.

The idea is to help your camera simultaneously capture detail in both bright and dark areas of the scene.

When to use a GND filter?

You can reduce the exposure difference of the scene

GND filters don't subtract light evenly on all surfaces. As its name suggests, they subtract it gradually. This means that there are certain areas of the filter that subtract more light than others.

So you can decide on which area of the frame you want to subtract more (or less) light. This is particularly useful in scenes where the light gradually changes within the frame. For example, in scenes where the upper area is brighter than the lower area. Or one side has more light than the other.

By placing the darkest area (the one that subtracts more light) over the highlights of the frame, your camera is able to correctly capture a high contrast scene. In other words, with just one shot you'll be able to capture detail in both the highlights as in the shadows.

Without the GND filter, the highlights will probably be blown out or the shadows will be clipped. You have to decide whether to correctly expose one area or another.

With the filter you can darken the brightest area, so that the difference between the brighter and darker areas is smaller. Therefore, you'll be reducing the dynamic range of the scene.

They are called graduated neutral density filters because:

- Their density varies gradually, subtracting light gradually.

- From the bottom edge of the filter to the center, this gradual variation goes from transparent to a neutral gray tone.

- From the center to the top edge of the filter, this gray's density gradually increases, subtracting more and more light.

To summarize, they are sunglasses for your lens whose crystals have a progressive tint.

Although some photographers consider that filters are an artificial tool that alters reality, the truth is that a graduated neutral density filter helps you get just the opposite: capture a photo that is very close to what your eyes see.

You can increase local contrast

There is another lesser-known advantage of GND filters: they allow you to increase local contrast. In other words, the detail and color of the image are improved.

This is because, as I told you, this type of filter reduces the dynamic range of the scene. One thing is linked to the other.

Let me explain it in detail.

And in order to do it, I have to refer to the exposing to the right (ETTR) concept.

In short, the camera doesn't capture the same detail in all tones. In fact, it always captures far more detail in the highlights than in the shadows.

This lack of information in the shadows makes it the area of the image where you get noise first and where you get less contrast. If you reduce the dynamic range of the scene, the shadows will become brighter, the sensor will capture more information, and the contrast will be higher.

You don't have to use a GND filter in extreme situations: you can also use a GND filter in scenes where the dynamic range doesn't exceed that of your camera. Imagine a spectacular sky full of clouds. The filter can accentuate the detail of the clouds, or it can darken them and increase their clarity compared to the rest of elements.

Actually, as you'll see later on in section 8, their uses are (almost) endless.

But before explaining real examples, let's take a look at the different GND filters that you can find on the market.

GND filter chart

Remember that the GND filters mission is to control how much light you want the sensor to capture. So, depending on the amount of light you want to subtract, you should choose filters of different densities.

The most popular filters have 2, 3 and 4 stops.

In the GND filter table below you have the naming according to the filters' brand.

| Filter | Light reduction (stops) | Density |

| GND2 | 1 | 0.3 |

| GND4 | 2 | 0.6 |

| GND8 | 3 | 0.9 |

| GND16 | 4 | 1.2 |

| GND32 | 5 | 1.5 |

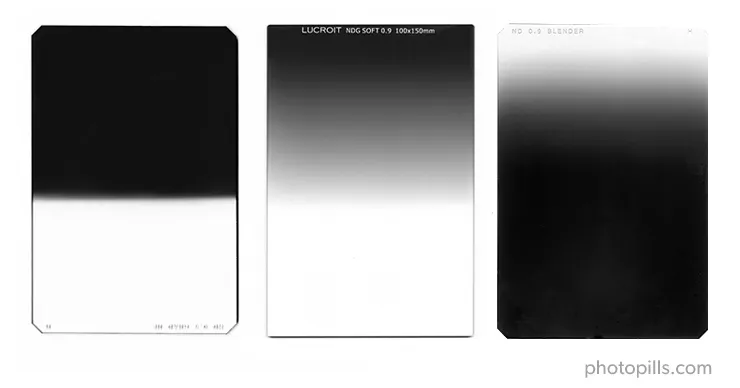

Types of GND filters according to the transition

Not all filters have the same transition from the darkest part to the clearest or more translucid part.

The transition can be hard, soft or diffused.

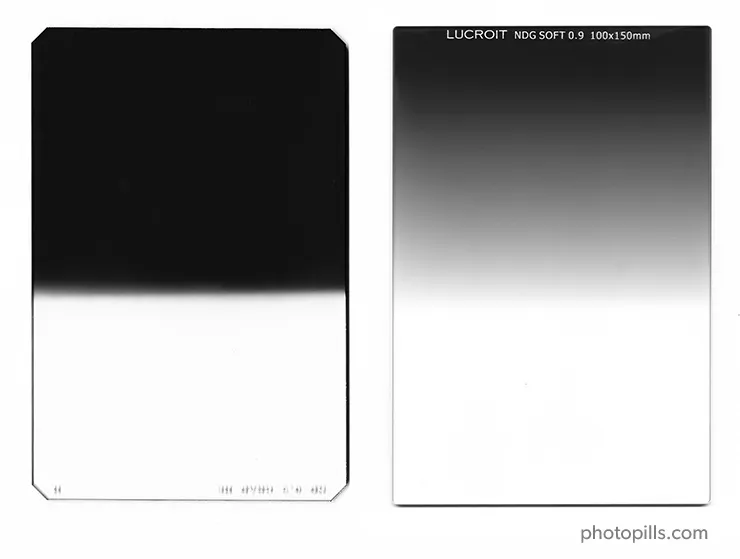

Hard graduated neutral density (GND) filters

In hard GND filters the transition between the dark and the transparent part is clearly marked with an almost perfectly defined horizontal line.

You can see it perfectly if you hold a filter with your hand and put it in front of a light source.

They will be very useful when your scene has a clean horizon (i.e. there are no elements above the horizon). Or when the scene has a clearly visible straight line separating light and dark tones.

Soft graduated neutral density (GND) filters

In soft GND filters, on the other hand, the transition is gradual: the dark part gradually becomes transparent.

These filters are ideal when you have elements above the horizon. In other words, when you can't see a clearly visible straight line in the scene that separates the brighter tones from the darker ones.

A soft GND is also ideal to use it over the sky during Sunrise or Sunset. When you have soft clouds during Sunrise or Sunset, they are barely colored. Thanks to the graduated filter, you can have much more saturated clouds.

Unfortunately, filter manufacturers don't agree on standard gradient values (i.e. how fast the filter changes from dark to transparent). So the filter gradient can vary significantly from brand to brand.

Blenders (diffused graduated neutral density filters)

A blender GND filter is completely dark at the top (almost as if it were an ND filter) and completely transparent at the bottom. The difference with the previous two is that the density gradually changes along the entire length of the filter.

In other words, if you look closely you won't see a "border" or a "transition zone" between the darkest and brightest part.

This type of filter is not very popular, but is very useful in scenes where there is a wide dynamic range but the highlights and the shadows are not clearly separated.

If you're shooting in a forest, for example, this filter is ideal. The light is filtering through the treetops while the trunks completely stop the light from passing through.

What is the disadvantage of using graduated filters?

A graduated neutral density filter may limit your composition.

Alas, it can.

The problem is that all (or some) elements above the horizon may appear in the final image darker than the rest of the scene.

You can solve this problem with a post-processing software like Photoshop. But in order to do so, you must know how to use luminosity masks, for example.

However, you should ideally avoid, if possible, using additional tools. I don't think you'd rather spend more time in front of the computer than taking pictures.

The most popular brands of GND filters are Lucroit, NiSi, Lee, Benro, Hitech and Haida.

If you're interested in buying lens filters:

- You can find my suggestions on the must-have lens filters in section 3.

- I tell you everything about the best lens filters in section 4.

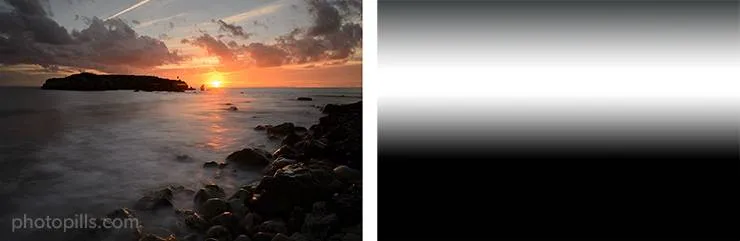

Reverse graduated neutral density (reverse GND) filter

What is a reverse graduated neutral density (reverse GND) filter?

The reverse graduated neutral density, or reverse GND filter, is a variation of the graduated filter.

Its peculiarity is that the darkest part, the one that determines the filter density, is in the middle of the filter, and it progressively brightens towards the top. On the contrary, the lower half is completely transparent (to avoid subtracting light in the foreground).

That's why it's called reverse.

When to use a reverse GND filter?

You can mainly use it for photographing backlit Sunrises and Sunsets with a clean horizon (without elements above).

Imagine you're on a beach trying to capture a beautiful Sunset.

The Sun sets creating a strong light and you decide to adjust the exposure so that the highlights (i.e. the Sun) aren't blown out in the histogram.

As you can see, the problem is that the sky looks great but the rocks are very dark. Too dark...

So you can try to change the exposure and adjust it to the shadows so that they don't turn out so black.

And that's ok. The problem is that by making this decision you've decided to sacrifice the highlights and now they are completely blown out. Not even your favorite software is able to recover them: the RAW doesn't have that information and that area of the photo is completely white.

Can you solve the issue with the bracketing technique?

A bracketing can be incredibly useful on many occasions. But not always..

Unfortunately, in this case you have to take into account a small detail: the movement of the water. No matter how hard you try, you'll never get 2 (or 3 or whatever) totally identical shots whose only difference is the exposure.

So it will be very (very) difficult to merge them later in Photoshop without halos and other elements that distort the image.

Be careful. I'm not saying it's not possible. It's just complicated.

Can you use a soft (or hard) GND filter instead?

Another option can be to use a soft (or even hard) GND filter to balance the exposure of the scene and use the dark part to mitigate some of the highlights.

However, the resulting photo isn't exactly what you're looking for, is it?

The top of the sky is too dark while the Sun doesn't have enough detail. The overall exposure of the image still doesn't match what your eyes see.

Let's go back to the first shot you took and let's identify the bright and dark areas.

Using the light map as a reference, compare it with the effect of a soft GND filter and a reverse GND filter.

Can you see the problem?

In this case you're facing a scene where the horizon is almost straight and you have hardly any obstacles.

When you try to capture a Sunrise or Sunset, the brightest (or clearest) part of the scene is not at the top of your frame. If so, a soft GND filter would be perfect.

The brightest part of your scene is in the middle of your frame.

Now, look at the diagram above and have a close look at a reverse GND filter. You can clearly see that the darkest part of the filter (the one that helps you counteract the brightest part of the frame) is right in the middle.

And when you use it... it works like magic!

So as you can see, a reverse GND filter can be a very useful tool in certain situations.

The most popular brands of reverse graduated filters are Lucroit, Nisi, Benro, Lee and Haida.

If you're interested in buying lens filters:

- You can find my suggestions on the must-have lens filters in section 3.

- I tell you everything about the best lens filters in section 4.

Ultraviolet (UV)

A few years ago, when most of us used film cameras, the ultraviolet (UV) filter had a very specific purpose.

Today, most photographers use it as a lens protection filter to prevent their lenses from breaking or scratches.

What is an ultraviolet (UV) filter?

An ultraviolet (UV) filter is a glass filter, usually circular, that you screw onto the front of the lens and blocks ultraviolet rays.

When to use a UV filter?

A UV filter is generally used, as I said before, to block ultraviolet rays. It's the equivalent to a sunscreen protection for your camera.

Back in the days of film photography some films were very sensitive to ultraviolet light. So if you didn't use a UV filter, you could end up with a blue cast affecting the exposure and color temperature of the pictures after developing them. Obviously, this problem was even worse if you took pictures on a very sunny day or at a relatively high location above sea level.

The fact is that modern films and digital sensors of any DSLR or mirrorless camera have a UV filter over them that protects them from this type of light. So the UV filter has become basically useless.

However, many photographers still use it as a protection for their lenses.

Does a UV filter really protect your lens?

If you drop your brand new €2,500 lens, the UV filter (which cost you €20) will break instead of the front glass of your lens. And, obviously, it would always be easier to buy a new filter than to send the lens to the official repair service to fix it, wouldn't it?

Yet, although it seems like a good idea, the truth is that in practice it's not quite like that.

The reality is that the glass of any UV filter is much more fragile than the front glass of any lens. So if your lens falls, the UV filter is going to crack while the front glass of your lens will remain safe and sound.

On top of it, if you hit or drop a lens strongly enough to damage the front glass, your lens will suffer some internal damage as well. So, even if the UV filter had protected the front glass, the lens would still be damaged.

In short, if you drop your lens with a UV filter and only the filter breaks but not the lens, all you did was breaking a filter. The lens would have survived in any case. And if you drop your lens without a UV filter and it breaks, an UV filter wouldn't have prevented it.

"But Toni, does that mean that UV filters offer no protection at all?"

No. The bottom line is that they offer no protection against impacts. But they do protect your lens from dust, scratches, sand and other small threats.

The negative effects of a UV filter

One last thing.

Don't forget that putting any glass in front of your lens will negatively affect the quality of the image.

A UV filter blocks a small percentage (between 0.1% and 5%) of the light that goes through it. The effect the filter has on the light slightly reduces the sharpness and contrast of your images. It's a barely noticeable effect that can be easily fixed with Lightroom or Photoshop, but you should be aware of it.

Unfortunately, that's not it...

A UV filter can also cause flare or halos if you're photographing a scene with a bright light source, especially in low ambient light or night photography. In these cases the flare is much more visible.

In addition to this, exposing your lens to UV rays helps to eliminate any fungus that may have grown. If you always have a UV filter screwed onto your lens, the chances of having fungus in your lens are much higher: moisture can slip between the lens front glass and the UV filter and fungus can create a great home XD

Should you use a UV filter?

Actually, it depends. Although I admit that I am not very fond of UV filters, I never use them.

Before you buy a UV filter and put it in front of your lens, keep in mind that:

- A UV filter will protect your lens from dust and scratches at best. It might be a good idea to use one on the beach or in the desert. But in most cases, it's best not to use it.

- UV filters have a small negative impact on your image quality. Most of the time, you won't notice the difference. But if you're looking for the best possible image quality, or if your photos show flares and halos, don't use a UV filter.

Light pollution filter

Sodium vapor bulbs are generally used in all types of public (streetlamps) and industrial lighting. They're one of the most frequent sources of light pollution.

This type of bulb has a yellow to orange glow that modifies the color temperature and significantly reduces the contrast of a night photography.

A light pollution filter allows you to prevent artificial lights in urban centres from affecting your night photography or astrophotography.

Can you notice the difference?

It's usually made of didymium glass. This material is capable of reducing the yellow and orange glow in such a way that the color temperature and contrast of your pictures are closer to reality.

If you've ever tried to take pictures of the Milky Way or Star Trails, you've seen the horrible effects of light pollution. I'm sure your photos have a sky with an orange cast that ruins everything, reduces contrast and doesn't let you perceive the real color of the stars.

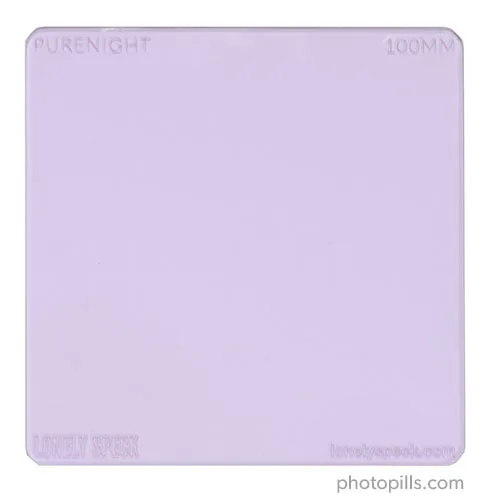

Once you use a light pollution filter you'll see the difference. I have the Pure Night filter designed by Ian Norman and since I bought it, I always carry it in my backpack whenever I go out to take pictures at night.

The introduction of LED street lights throughout the world over the last few years has brightened the sky up significantly. Unfortunately, energy-efficient LEDs are more difficult to block with a light pollution filter of the kind.

Even though the move to LED's is worrying, it would seem that the filter manufacturers still have a few methods of reducing this type of light...

Therefore, make sure you get a filter that does a better job of blocking the modern white LED lights found in the city.

Solar filter

A solar filter is specially made to photograph the Sun or a solar eclipse.

Don't risk damaging your eyesight and equipment by using some cheap filter or one not designed for looking directly into the Sun.

Your filter must also block infrared (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) light as well which, though invisible, can also damage your eyes.

What are the different types of solar filters?

There are three types of solar filters for photography:

- Aluminized Mylar®

- Metal-coated

- Black-polymer (usually handheld)

All the filters can be:

- Circular or square.

- Mounted in a metal cell, making it very easy for you to clamp them over your lens and adjustable to different diameters.

How are you going to see the Sun through a solar filter?

Aluminized Mylar® filters are the most expensive ones. However, they provide a white Sun which is true to the Sun's real color (Surprise! It's not yellow).

Don't be deterred by their wrinkled surface. This surface tends to scatter light a little bit.

But these filters are actually very sharp. They're particularly good for highly magnified images.

Metal-coated glass filters and black polymer filters result in a saturated yellow Sun. Any of them will work fine, since you can always change the color of the Sun later on, in post-processing.

Finally, metal-coated glass filters offer you a sharper picture than black polymer filters which are more appropriate for naked eye observation and wide-angle images.

Don't use homemade filters!

According to NASA, the following materials should never be used to view a solar eclipse:

- Photographic polarizing filters

- Sunglasses of any kind

- Negative film (exposed or not)

- Smoked glass

- Space blankets and other forms of household Mylar, or silvery CD/DVD disks

- Medical X-ray film

- Floppy disks

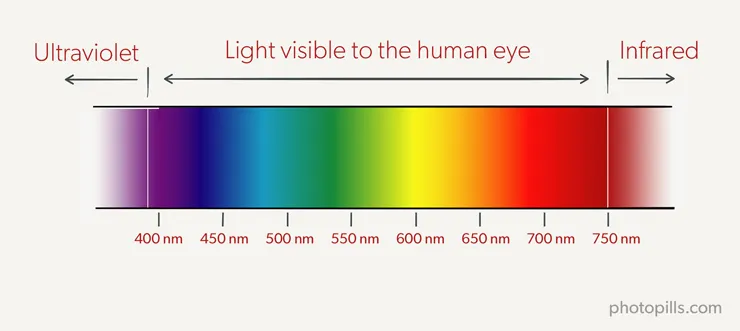

You must avoid them because, while they dim visible light, they don't block infrared (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) light that can damage your retinas.

If you want to photograph a solar eclipse, I suggest you study 'Solar Eclipses: The Definitive Photography Guide'.

The only problem is that a total solar eclipse is not very frequent. But you can always capture a lunar eclipse: 'Lunar Eclipses: The Definitive Photography Guide'.

Black card

A black card is actually nothing more than that. It's literally a piece of black card or any dark element that has a smooth, flat surface.

What is it for?

Very simple: to cover (totally or partially) the lens during the shot.

You can do this either if the lens is "naked" or if it has one or more filters in front of it.

When to use a black card?

Basically when you want to block light :)

For example, if you're photographing a lighthouse, you can use a black card to cover the lens each time a beam of light hits the lens.

But you don't always have to cover the lens completely. With a bit of skill, a black card allows you to control the exposure of that specific area of the scene where the highlights are too bright. You'll avoid blowing them out and your camera's sensor will capture enough information in the RAW file.

What are the drawbacks of using a black card?

The first and most obvious one is the lack of precision. It's a task you'll have to do manually. Remember that you will be handholding the black card (without the help of a filter holder) in front of the lens.

What does that mean?

On the one hand, you'll have to use the "try and fail" method to know how long you have to cover the lens.

On the other hand, you'll have to adjust the position of the black card. In other words, which part of the frame you want to cover. And be careful, because you'll have to make sure you move the black card slightly during the exposure to avoid having a black strip in your photo.

Moreover, depending on the shutter speed you're using, you may need to cover two sections of your frame.

Actually, you set the limits ;)

The second drawback is that you'll only master this technique by spending time practicing.

It's a craft, not a scientific technique so the results are not guaranteed. You'll have to try and see the results.

Infrared filter

What is infrared photography?

Infrared photography produces very interesting, generally impressive and incredibly creative results, as the objects in a scene reflect infrared light very differently from normal light.

In order to get these results you need (surprise!) an infrared filter. This filter is specifically designed to block visible light. That is, the light your eyes see and the light your camera's sensor is able to capture.

So it only allows infrared light to go through the lens and reach the camera's sensor.

To give you a simple explanation, the light you're able to see with your eyes is between 390 nm and 750 nm within the electromagnetic spectrum. Everything outside that range is "invisible" to you. This includes infrared, gamma, X, ultraviolet, microwave and radio waves.

Types of infrared filters

Just like the other filters, an infrared filter can be circular screw-on or square. Here, we are talking about external filters.

There are many models of external infrared filters, although the most common one is the standard infrared 720 nm (RM72) which is the one I use.

But there are also internal infrared filters. That is, a filter that you can put directly on the sensor as I did with my Nikon D300.

Actually, I asked a professional to do it. The first time I tried to do it myself with a Nikon D70 and I broke it... XD

I learnt the lesson and decided to send my Nikon D300 to Lifepixel (a US company) to put in a standard internal infrared filter.

Check that your camera can take infrared photos

Before you buy an infrared filter, make sure your camera can take such pictures. You can do a very simple test to confirm it.

Turn on your camera and put it in Live View mode. Grab the remote of your TV, point it at your camera and press several buttons on the remote.

If you're able to spot a bright red dot on the LCD screen, your camera can capture infrared light correctly.

If the red light is dim, your camera can capture infrared light. But you will need a very slow shutter speed because the sensor has a very powerful filter against infrared light.

Finally, if you don't see any red dots on the LCD screen, your camera is not capable of capturing infrared light.

Check that your lens is suitable for infrared photography

One more thing.

Not all lenses are suitable for infrared photography. This is due to certain optical problems. But I don't want to go in depth in Optics and Physics matters, so I'll leave it here.

The only thing you need to know is if your lens is suitable or not. This complete database will help you solve the issue.

Other special lens filters

Apart from all the filters mentioned above, there are a few special lens filters that I would also like to talk about.

Who knows? You might be interested in using them as well.

SharpStar2 lens filter

I've been following the work and progression of Ian Norman for several years now. He's also a very good friend of mine and an amazing PhotoPills Master.

His passion for astrophotography has led him to create a very useful lens filter called SharpStar2.

This lens filter is basically a focusing aid, especially if you're having difficulty in achieving consistency in sharp, focused stars. All you have to do is to align the middle diffraction spike in the center of the two diffraction spikes on either side.

If you're tired of the lack of consistency in achieving sharp, focused stars using a manual focusing technique, this lens filter is for you.

In addition to this, focus can be achieved long before the sky gets dark if you have a bright enough star or planet.

Gold-N-Blue (Singh-Ray) and Varicolor Blue/Yellow (Cokin) polarizer

What is a color CPL filter?

Now that you know what a circular polarizing filter is and what it's for, let me surprise you by explaining a few things about the Gold-N-Blue circular polarizing filter (Singh-Ray) and the Varicolor Blue/Yellow de Cokin.

At this point, you know that "regular" polarizers enhance color saturation on your images and also reduce or eliminate reflections (as long as they are not metallic).

But can you imagine that besides that the polarizer gave the sky or the water a warm and golden tone? Or a cold blue tone?

The difference in tonality will depend on the direction you rotate the filter. Instead of eliminating reflections, this filter colors them with an intense blue or yellow tone as you rotate the filter.

Can you get the same result with a color filter?

In case you don't remember, a color filter is used in analog photography, and more specifically in black and white photography. Depending on the color of the filter, greens, blues or reds are enhanced.

But they're also used in digital photography to change the color of a portion of the scene or the color temperature.

Back to the color circular polarizing filter...

The truth is that you don't get the same result with a color filter.

First of all because the materials' quality is not the same (a color filter is usually of low quality and very cheap compared to any polarizer), so the effect can hardly be the same.

And secondly, because any polarizer will always increase the contrast of the image, while a color filter will not.

However, you'll have to spend part of your savings in exchange for getting this nice effect on your photos...

What are the drawbacks of using a color polarizer filter?

- It's a (very) expensive filter compared to a high quality "regular" polarizer (the CPL I told you about in the previous section).

- It's not easy to use this filter. Because it's a screw-on filter, you can't use with any filter holder. If you also need to use an ND or GND filter at the same time, you'll have to handhold them in front of the lens.

- It produces a quite strong vignetting, so you shouldn't use it with other filters as you'll accentuate the vignetting.

- The filter has a strange effect on the color temperature of the photo. Don't use the auto white balance. Use the "try and fail" method and adjust the white balance manually. If you make a mistake, you can always correct it later on in post-processing.

Skylight lens filter

What is a Skylight filter?

A Skylight filter is a glass filter, almost always circular, that you screw onto the front of the lens. In addition to blocking ultraviolet rays, the filter has a faint orange-pink cast.

When to use a Skylight filter?

Like a UV filter, this filter is used with film cameras.

The effect of a Skylight filter is slightly warm. Thus, if you're using a film with a specific color temperature for outdoor day scenes, the filter counteracts the bluish cast that some scenes, especially indoor ones, may have.

Obviously, if you use this filter with a digital camera (although, in my opinion, it doesn't make much sense) and you have some color problem in your photos, you can always correct it in post-processing with a software like Lightroom or Photoshop.

The difference between a UV filter and a Skylight filter is that the first one is neutral (has no tint or color cast) while the second one is a basic color correction filter with a slightly magenta tint.

Perfect!

After this explanation on filters, which I hope you've used as a warm up, the fun is about to start!

Will you come with me?

It's time to figure out the lens filters you should always carry with you :D

3.What lens filters are essential?

If you're wondering...

"Should I use lens filters?"

The answer is YES.

There are tons of photography genres in which you need lens filters: landscape, night portraits, infrared, astrophotography, wildlife, black and white, outdoor, real estate...

So, basically, depending on the type of pictures you want to take, you'll need one filter or another.

"Great Toni. So, what are the must-have lens filters?"

Well, one question at a time... ;)

Let's start with the first one.

Why should you use lens filters in photography?

As a photographer I use these little pieces of glass for a multitude of reasons. Lens filters help me minimize glare and reflections, enhance colors, reduce light coming into the lens, and more.

Nevertheless, the most common one is for managing tricky lighting conditions when shooting.

In my opinion, lens filters are indispensable for capturing scenery in extremely difficult lighting conditions, especially when you want to include the Sun in your composition or when you want to photograph a high dynamic range scene.

When should you use a lens filter?

As I just mentioned, it actually depends on the type of photography you do.

For example, landscape photographers heavily rely on various filters, while street and portrait photographers rarely get to use them.

The following table is a summary of the options you have.

| Photography genre | Lens filters you can use |

|---|---|

| Daylight | CPL filter, ND filter, GND filter, reverse GND filter, infrared filter |

| Landscape | CPL filter, ND filter, GND filter, reverse GND filter |

| Sunrise | CPL filter, ND filter, GND filter, reverse GND filter |

| Sunset | CPL filter, ND filter, GND filter, reverse GND filter |

| Golden hour | CPL filter, ND filter, GND filter, reverse GND filter |

| Blue hour | CPL filter, ND filter, GND filter, reverse GND filter |

| Solar eclipse | Solar filter |

| Drone | CPL filter, ND filter |

| Milky Way | Light pollution filter, SharpStar2 filter |

| Star Trails | Light pollution filter |

| Meteor Showers | Light pollution filter |

| Night portrait | Light pollution filter |

| Night sky | SharpStar2 filter |

What lens filters are essential?

It all comes down to a simple question...

Which ND filter should I buy?

The best ND filter for daytime long exposure photography is the 6-stop ND filter (ND 1.8).

Why? A 6-stop ND filter is, in my opinion, perfect for taking shots in two time frames:

- From the Sunrise actually happens until 30 minutes after Sunrise.

- From 30 minutes before Sunset until the Sunset actually happens.

Other popular ND filters:

- 3-stop ND filter (ND 0.9)

- 8-stop ND filter (ND 2.4)

- 10-stop ND filter (ND 3.0)

Which GND filter should I buy?

The best GND filter for daytime long exposure photography is the 3-stop soft GND filter (GND 0.9).

Why? The 3-stop soft GND filter is certainly the GND filter I use the most. As for the transition (soft), this filter is perfect for landscapes (marine and non-marine) where the horizon line is straight (seascape) or nor (mountainscape).

Other popular GND filters:

- 4-stop soft GND filter (GND 1.2)

- 2-stop soft GND filter (GND 0.6)

- 3-stop soft reverse GND filter (reverse GND 0.9)

Which polarizer (CPL) filter should I buy?

The best polarizer (CPL) filter, in my opinion, is the 112mm Slim circular polarizer from Lucroit.

Why? This specific choice is based on the fact that quality-wise it is excellent and I can mount it on my Lucroit lens filter holder together with other three filters with no vignetting up to 14mm full frame equivalent.

4.The best lens filters in 2024

Here's the question I always get in my workshops:

"Toni, what lens filters should I buy?"

I have to admit that it's a difficult one.

There are tons of excellent lens filters in the market. So it's hard to pick one per category.

My first recommendation would be to buy the best quality lens filter glass you can afford. After all, adding a cheap lens filter in front of your expensive lens can have negative effects...

"OK Toni, let's get to the point. What is the perfect lens filter kit for beginners?"

Fine, fine...

Here are the best lens filters for beginners!

Best polarizing filters

These are what I consider the best CPL filters:

- The B+W Kaesemann Circular MRC 77mm polarizing filter.

- The 112mm Slim circular polarizer from Lucroit.

- The 165x165mm square polarizer from Lucroit.

Best ND filter for daylight long exposure photography

These are my favorite ND filters (choose the 100x100mm or the 165x165mm version depending on your lenses):

Best graduated neutral density filter

This is the best graduated nd filter or GND filter (get the 100x100mm or the 165x165mm version depending on your lenses):

- The Lucroit HQ 3-stop soft GND filter (GND 0.9).

- The Lucroit HQ 3-stop soft reverse soft GND filter (reverse GND 0.9). Perfect for clean horizons! ;)

5.How to use the polarizer filter

What is a polarizing filter?

Although I told you a few things about the polarizer in section 2, now I would like to explain to you in more detail how to use it.

You surely remember that in photography we use a circular polarizing filter (CPL).

To use it, all you have to do is rotate it and you'll see how part of the scene becomes "polarized". And if you rotate it in the opposite direction, it "depolarizes".

And I write "part" because it's a filter that partially acts on the scene. When you use it you have to decide which part of the scene you want to polarize.

Basically, a CPL filter helps you:

- Eliminate most of the light reflected in your scene. Therefore, the saturation and contrast of your photo increases.

- Reduce haze.

- Make reflections disappear (as long as they are non-metallic). Or enhance them.

How much light the polarizer (CPL) filter subtracts?

Like any other filter, the polarizer is a filter that subtracts some of the light that enters through the lens to the sensor.

How much light?

It depends on the manufacturer and the model, but it usually subtracts is between 1.5 and 2 stops.

When the CPL filter is polarizing at its maximum, it's subtracting the maximum number of stops. It actually subtracts light in the whole scene, although it does it more vividly in the areas where the non-metallic reflections are eliminated.

But if you haven't rotated it to its maximum, and you've left it at an intermediate point of polarization, the filter will be subtracting a little less light.

You can see its effect with the naked eye.

Take your circular polarizing filter and stand in front of a light source. Look through the polarizer filter. Now, rotate the ring very gently with the other hand. See how it gets darker?

Because it's so gradual, it's hard to tell exactly how many stops it subtracts. At the same time, this allows you to make very precise adjustments and polarize a lot, a bit, or just a tiny little bit (as much as you want!).

How to use the polarizer (CPL) filter

In this video, I show you how to use a polarizing filter.

But if you prefer reading, here is a step by step explanation.

Let's see the workflow you have to follow to use the polarizer.

1. Mount the polarizer in front of the lens

Depending on the system you use and the shape of the polarizer filter (circular or rectangular), the mounting system will be different:

- If it's a circular polarizer that matches the lens diameter, screw it on carefully and try not to leave fingerprints on the surface.

- If it's a circular polarizing filter that doesn't match the lens diameter, screw it into the filter holder ring. Be careful not to leave fingerprints on the surface. Then, put the ring in the filter holder. Depending on the brand you're using, the polarizer may be closer or further away from the sensor.

- If it's a rectangular polarizer, insert it into the corresponding slot on the filter holder. This is usually a slot, other than those enabled for ND and GND filters, or a specific holder.

2. Turn the filter carefully until you get the desired effect

If you have a mirrorless camera (with an electronic viewfinder) or a DSLR with this option, turn on the live histogram.

The key to using the CPL filter is the angle.

In other words, how much you have to rotate it to get what you want.

Fortunately, the procedure is very simple and much more intuitive than you imagine.

Once you're happy with your composition, all you have to do is rotate the filter gently. Do it little by little.

In the meantime, check the Live View LCD screen, or your electronic viewfinder if you have a mirrorless camera, to see if you're getting the effect you want. And if so, if the filter is doing it with the intensity you're looking for.

Imagine, for example, that you're photographing a seascape and you want to see the detail of the seabed in the area closest to the shore (foreground). Rotate the polarizer slowly. If you see the water becoming more and more opaque, rotate it in the opposite direction and you'll see how the rocks and sand of the bottom magically appear.

Now suppose you want to add contrast to the sky and highlight the volume of the clouds. In this case, the best moment is with the Sun at a 90º angle with respect to the direction you're pointing your camera to.

So you need to have the Sun either to your left or to your right. That's how you get the maximum possible polarization of the sky.

3. Meter the light to adjust the exposure and focus

Now that you've determined how, where and how much the polarizer affects the scene, it's time to meter the light in the key tone of the scene (with the polarizing filter on).

Remember that, depending on the polarization angle, the filter subtracts between 1.5 and 2 stops. So you'll have to adjust the exposure according to what you want to achieve.

If you have a mirrorless camera (with an electronic viewfinder) or a DSLR with this option, use the live histogram to help you adjust the exposure precisely.

Finally, focus. If you use the autofocus (and you're not using the back button focus), don't forget to change it to manual once you're done to avoid refocusing by mistake by pressing the shutter button...

4. Take the shot and check the result

If you didn't get the polarization effect you were looking for, carefully rotate the CPL filter ring (or the filter itself, if it is rectangular) back until you do.

If the photo doesn't have the exposure you were looking for, adjust one of the exposure triangle settings.

Before I finish, let me remind you a couple of things.

First, you should avoid using a polarizing filter if you're going to use a wide angle lens and/or if you're going to take a panoramic photo. Keep in mind that you'll be covering an extremely wide angle of the scene and the polarizer won't be able to cover it completely. You'll have halos or flares in the picture.