Exposure in Photography: The Definitive Guide - Chapter 2

Get this ebook for free now!

Content

Chapter 1

- 15 quick answers to 15 questions about exposure

- It all starts with light

- What's exposure?

- Caution! The exposure serves your ideas (not the other way round)

- Understanding the exposure triangle

- The stop and how to use it

- The reciprocity law and some examples

- What's the exposure value (EV) and what is it for

- Scene dynamic range vs your camera's dynamic range

Chapter 2

- Check the exposure, examine the histogram

- Your allies (the light meter and the handheld photometer)

- Your camera's light metering modes

- Your camera's exposure modes

- How and when to use the exposure compensation (±EV)

- How and when to lock the exposure (AEL o AE-L)

- Be careful with the light meter (it sees everything at an 18% grey)

- Expose your histogram to the right (ETTR)

- How to expose step by step

- How to expose without a light meter: the "Sunny f/16" and "Looney f/11" rules

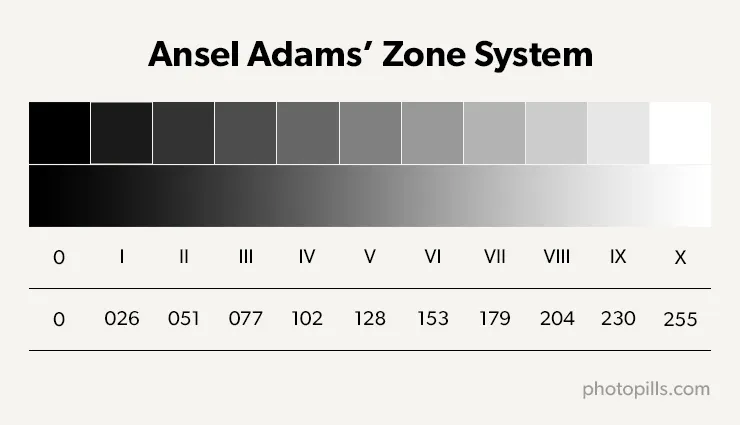

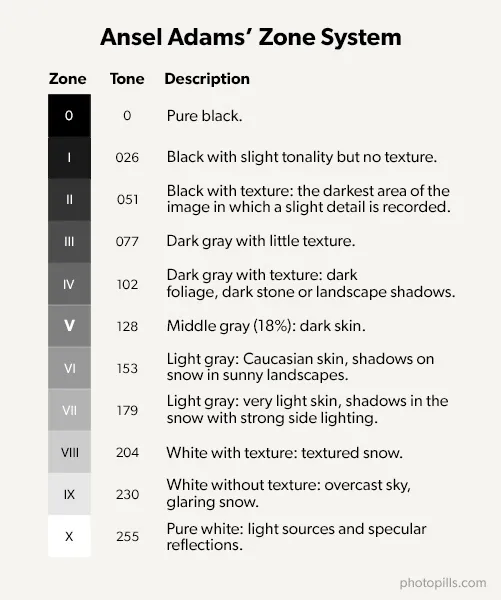

- How to expose with the Ansel Adams zone system

- How to expose a video

Chapter 3

- Use filters to successfully capture high contrast images

- Use auto exposure bracketing to successfully capture high contrast images

- 30 practical examples of exposure

- The 12 mistakes you should avoid when exposing

- 10 amazing photographers to inspire you and learn how to expose

- Your time has come...

Chapter 2

10.Check the exposure, examine the histogram

Imagine you are in front of the perfect scene, you take the camera, you meter the light (section 12), you set the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings... You frame, you focus and you shoot.

You look at the photo and you hesitate. You're not sure if part of the image has been overexposed (or underexposed).

Would you like to clear up any doubts?

Well, check the histogram of the photo that the camera produces.

What's the histogram and what's it for

The histogram is a statistical graph that represents the scene tones (or brightness levels) captured by the camera.

In other words, it gives you information about the tones that appear in the photo (how dark or clear is a color).

And why is it useful?

Because it lets you know if a picture is well exposed or not. It clearly tells you if you're overexposing (when the histogram touches the right edge of the graph) or underexposing (when the histogram touches the left edge of the graph) some areas of the scene.

On the other hand, it also lets you know if your camera is capable of capturing the entire dynamic range of the scene.

You'll understand it better if you see how your camera generates the histogram of a photo.

How the histogram is produced

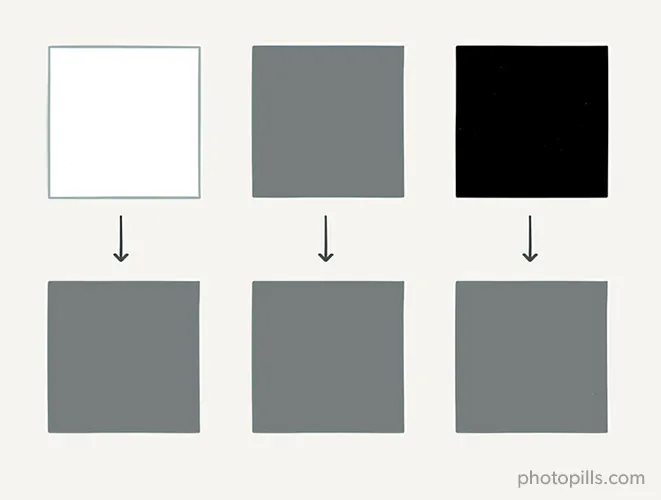

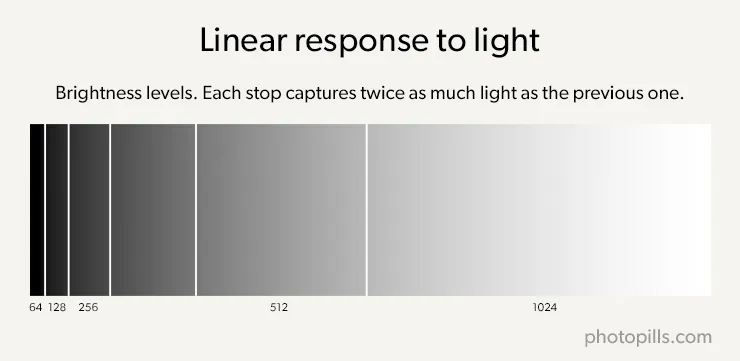

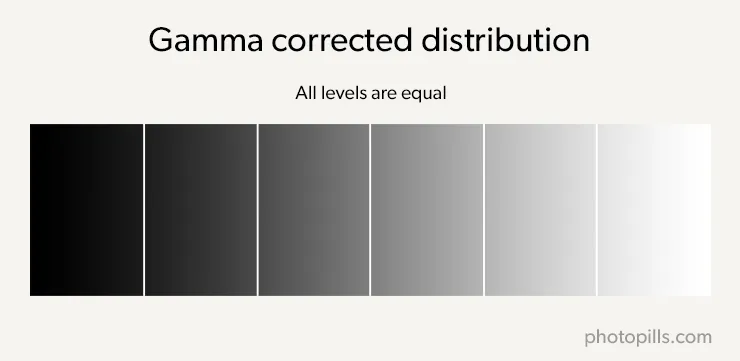

Each photo you take is composed of pixels. The camera picks up the tone of each of those pixels, regardless of color. When I say tone, I mean its luminosity. Are they bright, are they dark?

It then turns them into white, black or in different shades of grey, depending on how bright or dark the tone is. Normally, the camera uses up to 256 light values (also known as levels) to generate the histogram.

Once it has converted the last pixel of your photo, the camera counts the number of pixels of each tonality and builds a bar chart.

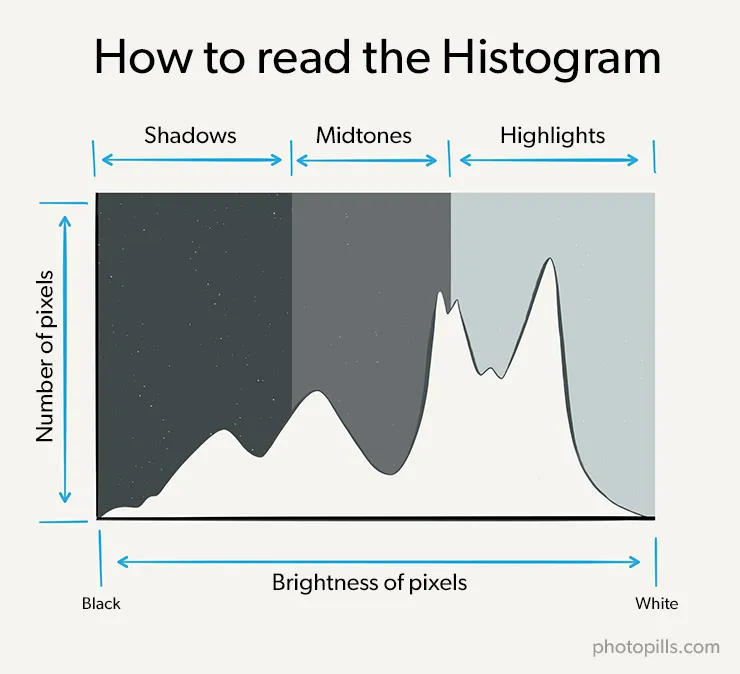

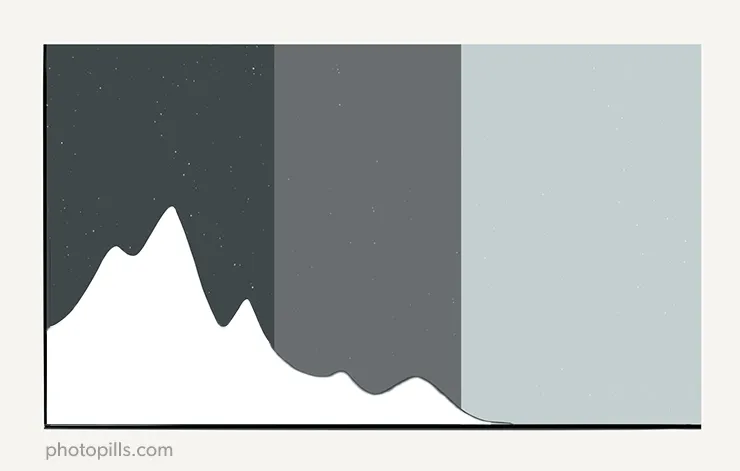

This bar chart or histogram has two axes:

- The horizontal axis (x) represents the tone of the color. Pure white is at the far right of the histogram and pure black at the far left.

- The vertical axis (y) shows the number of pixels with that tone.

Therefore, the more a tone is repeated in the image, the higher the bar of that tone in the histogram is.

How to read the histogram

The histogram is a crucial tool to expose your photographs. So you must learn to read it, to interpret it.

Along the horizontal axis (x) and from left to right you have:

- First the black tones, with pure black on the left edge.

- Then come the shadows.

- Then the midtones.

- Followed by the highlights.

- And finally, the white tones, with pure white on the right edge.

The histogram shows you all the light values the camera has been able to capture in a certain scene and in a single shot. In short, it shows you how the tones that fit within the dynamic range of the camera are distributed.

In other words, between the tone located at the left end of the histogram and the tone at the right end there is a certain number of stops. This number of stops corresponds to the dynamic range of your camera.

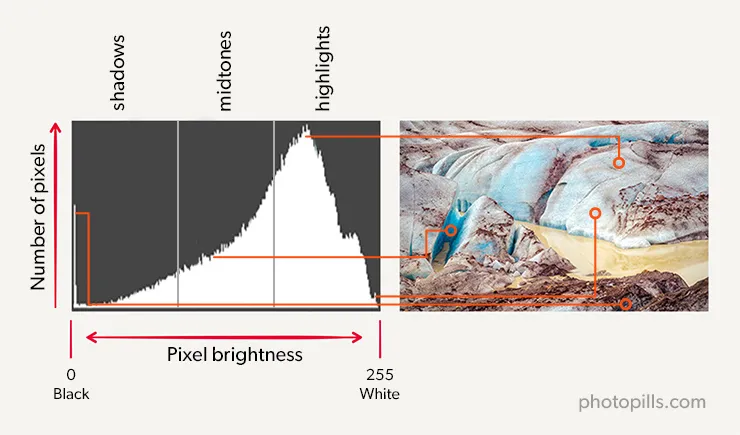

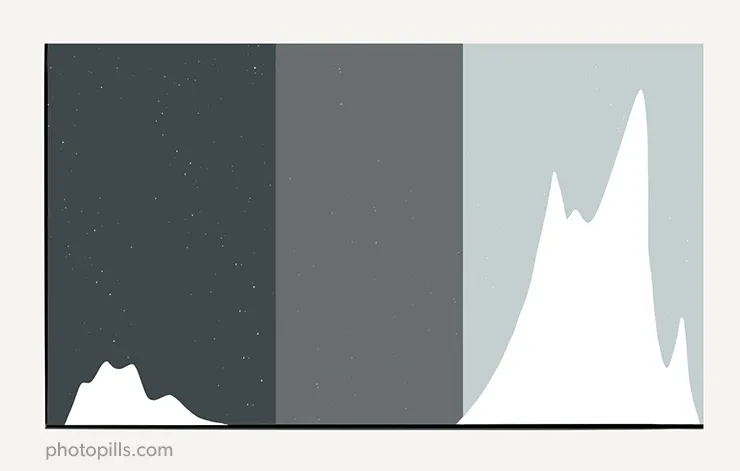

Let's have a look at an example. Look at the following picture and its corresponding histogram. There you can observe the tonal distribution.

Where to find a picture's histogram

Each camera is different. Some cameras show you the histogram right after you take the picture. Others don't.

Mirrorless cameras, for example, let you decide to see a live histogram in a corner of your electronic viewfinder. This option is very useful and makes the shooting a lot easier. You can modify the settings while you are looking through the electronic viewfinder and observe the changes before pressing the shutter release button.

I suggest you take a look at the instruction manual of your camera to find out how to display the histogram of a photo.

How do you know if a picture is overexposed or underexposed?

The histogram lets you know if a photograph is well exposed or not. It clearly tells you if you are overexposing (when the histogram touches the right edge of the graph) or underexposing (when the histogram touches the left edge of the graph) some parts of the scene.

It also lets you know if your camera is capable of capturing the entire dynamic range of the scene.

Usually, a correctly exposed scene has a histogram that doesn't touch the right or left end or, if it does, it is minimally.

I say "usually" because sometimes you can be interested in (or you may have no choice but to) overexposing a part of the image. The typical example is backlighting.

The truth is that there isn't a specific or standard histogram shape that tells you if the photograph is correctly exposed. It all depends on your artistic criteria as a photographer and the tones of the scene.

But for the sake of simplicity and as a rule of thumb, you can consider that a histogram is correct if it's centered or slightly shifted to the right. Nevertheless, remember that there is no correct exposure as I explained in section 3.

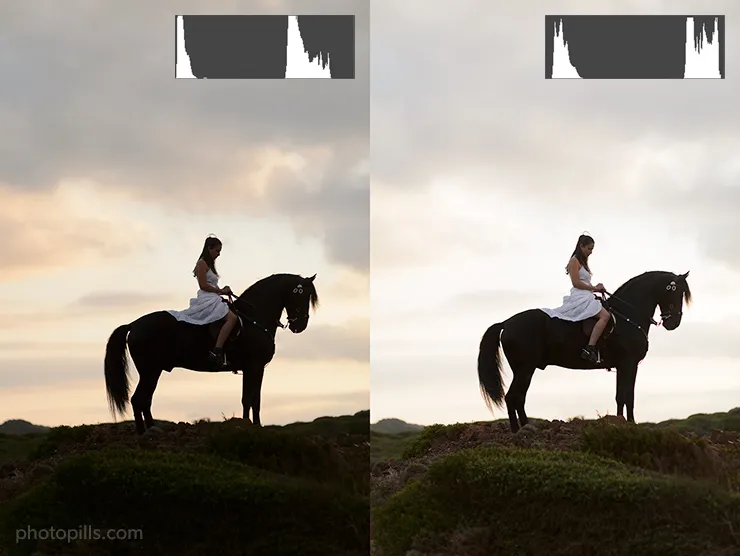

Check how the exposure changes depending on the histogram in the following photos.

Histogram with two tones clearly separated

Avoid blown out highlights and clipped shadows

When it comes to exposing correctly, you have to face two enemies: blown out highlights and clipped shadows.

In both cases your camera is not able to capture all the information in the scene. And the problem is that you're missing detail in the photo. You're losing image quality.

Blown out highlights

If your image produces a histogram that is touching the right edge of the graph, it's overexposed. What's happened is you've lost information because one or more areas are completely white.

In other words, part of the image has been burnt out or, as photographers say, highlights are blown out.

In this case, unless that's the result you're looking for, you can:

- Reduce the exposure through the exposure triangle (aperture, shutter speed, ISO), capturing less light overall in the photo and preventing the histogram from touching the right side.

- Use a neutral density filter (ND) to capture less light (section 22).

- Use a graduated neutral density filter (GND) to capture less light selectively in the scene. For example, by overlapping the darkest part of the filter with the clearest area of the sky (section 22).

- Shoot multiple exposures to blend them in post-processing (section 23) or capture a high dynamic range (HDR) image straight out of your camera.

As if this were not enough, you should also be careful with the specular highlights!

Specular highlights are glitter or very bright spots that usually appear on shiny (and wet) surfaces on sunny days.

In fact, every time you try to photograph a glowing object with a lot of Sun you'll see specular highlights in your photo.

For example, take a picture of a car and you'll see specular highlights in parts of the body or other metallic elements as a result of a strong light source reflected in them. The body is acting like a mirror reflecting the sunlight.

And as you may have already guessed, these highlights are completely overexposed: the image highlights are blown out.

Another element that can cause specular highlights is the flash. If you shoot against a reflective surface, the light produced by the flash will bounce and will create these highlights.

To avoid against specular highlights you can do the following.

If you are outdoors, the best solution is to use a circular polarizing filter (CPL). I'll tell you more details about other types of filters in section 22, but you should know what it is and what it can do for you.

A circular polarizing filter (CPL) is a circular piece of glass or resin surrounded by a metal structure. On the one hand, the metal structure has a thread so you can screw the filter to your lens. On the other hand, it has a wheel that, when you turn it, increases or reduces the filter's polarizing effect.

What do you achieve with a circular polarizing filter (CPL)?

- Limit the glare and reflections of all surfaces except metal surfaces.

- Limit the reflection of glasses, window shops...

- Other effects like saturating the green tones or darken the sky.

The filter is circular and threaded, so its diameter must be the same as your lens one.

If you are indoors, specular highlights are difficult to avoid due to artificial lighting. But you can play with them to your advantage or at least limit them.

For starters, don't point the light source directly to your subject. Make it bounce on a surface (the ceiling, for example) or use an accessory like a diffuser.

Also, try to have a light source as large as possible. The light will be more diffuse and softer.

In doing so the reflections' edges won't be very bold, they will be mixed up with the surrounding areas and they will be less intense.

If you use a flash, the most important thing is to avoid using a hard light. In this case, use a diffuser for example.

And try to avoid pointing the flash to your subject. If you modify the light beam and bounce it on a surface (a wall, for example), this light will cause fewer reflections and highlights.

Clipped shadows

Your second enemy are the clipped shadows.

Contrary to what happens with blown out highlights, here the histogram is touching the left edge of the graph. In other words, the photo is underexposed.

What's happened is that you've lost information from the scene (no detail is shown) because one or more areas are completely black. In other words, the shadows are clipped.

In this case, unless that is the result you are looking for, you should:

- Increase the exposure using the exposure triangle (aperture, shutter speed, ISO) by capturing more light overall in the photo and preventing the histogram from touching the left side.

- Add artificial light with a flash, a flashlight or a LED. In night photography, you can use the moonlight to illuminate the foreground if you plan it in advance. To learn how to do this you can check out our guide 'How to Plan the Next Full Moon'.

Conclusion

An overexposed (blown out highlights) or underexposed (clipped shadows) image is caused by two different reasons:

You made a mistake when exposing the scene. You can easily solve it by simply exposing more or less, or using filters (in case the scene is overexposed). At the same time, you should try to make sure that the histogram does not touch either edge or, if it does, that it does so minimally.

The dynamic range of the scene exceeds the dynamic range of your camera. In this case you have no choice but to use other techniques such as the use of filters (section 22) or a bracketing (section 23), blending several captures into a unique image in post-processing. These solutions allow you to capture the full dynamic range of the scene by capturing information in both the shadows and the highlights.

Tips

- Most cameras have an display option set to show you on the LCD the areas of the image that are overexposed. They are the highlights alert blinks or "flashing blinkies".As the name states, these areas usually blink so you can quickly spot them. It's a very useful tool since the camera itself is telling you to change the exposure in order to capture detail in those areas.

- If you shoot in RAW, take into account that the histogram the camera shows you is produced using a JPG file created from the original RAW. This JPG file has being edited by the camera, applying the image style you have configured (standard, landscape, portrait or neutral, among others). Depending on the style you set, the histogram may tell you that you are overexposing or underexposing certain areas. However, once you come back home and see the RAW file on your computer, you may find that these areas weren't actually over or underexposed.The best solution is to use a predefined style (or create your own one). What you ideally want is that the camera produces a histogram as similar as possible as the one you get on your editing software. If you manage to do so you get an accurate result on your LCD after exposing.Most cameras have this option. All you have to do is create a user style of image and customize it according to your tests. To do this, adjust the histogram values to be as close as possible to what you see when you import your RAW files into Lightroom, CaptureOne, or any other editing software program.Obviously, these values are applied in camera but don't change or edit in any way the original RAW file. It's a setting that affects only the way the camera interprets the RAW file and how it's displayed on the LCD.In my case, I have all the histogram values set to 0. I shoot in a RAW format without any modification or customization. At the time of taking the photo, the only thing I adjust is the white balance because I like doing it manually.Then, in the Lightroom Develop module, I choose the "Neutral Camera" profile so that the image is accurate compared to what I saw on my camera's LCD. Sometimes, depending on the camera I used during the session, I choose the "Standard Camera" profile.Why do I do this? To avoid the Lightroom "Adobe Standard" default profile. This profile has very little to do with any camera's profile.As you can see by clicking on the drop-down menu, Lightroom offers you many different camera profiles (Standard, Vivid, Neutral, Landscape...). Even if you have two identical camera models, the software is able to differentiate them by their serial number.All you have to do is choose the profile that matches as much as possible the photo you saw on the LCD.

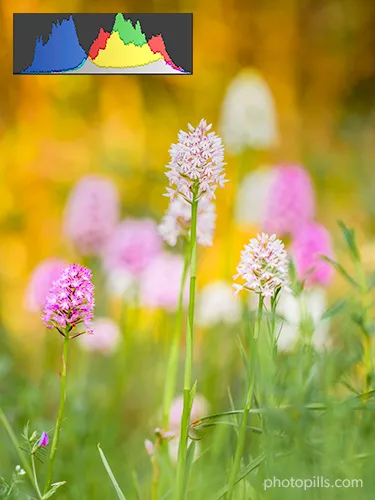

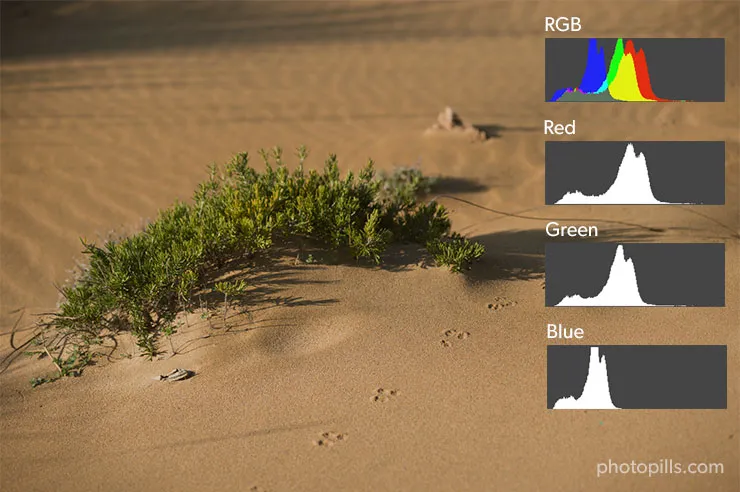

The other three histograms (or the RGB histogram)

At this point, you know what the histogram is. But, you should also know that most cameras allow you to display not one, not two histograms, but three!

Each histogram corresponds to a color channel: red, green and blue. R-G-B...

But let's take a little break before continuing with the different histograms.

What's this RGB thing?

RGB is an acronym consisting of the words red, green and blue.

It's a concept that usually refers to a chromatic model. This model represents different colors from the mix of these three primary colors.

When to check the RGB histograms

Back to the three histograms...

Should you check the three RGB histograms in each of the photos you take?

In most cases the answer is "no".

However, it can be useful if you are photographing a landscape during a sunset, the detail of some flowers or any element that has a very saturated color palette.

Depending on the scene, one of the three channels (red, green, or blue) may be overexposed and your camera's histogram (or the "blinkies") may not warn you.

In this case, the histogram is not enough and you should review all three RGB histograms.

Overexposing a color channel could result in a significant loss of detail in the highlights of some areas with a lot of color.

When you shoot RAW (you don't shoot JPG, right? Tell me you don't), you could get some of this detail back during the editing. Nevertheless, I won't fool you, it depends on your camera and how overexposed that particular channel is.

So when shooting very colorful subjects, check out the RGB histogram. If one of the histograms shows a peak touching the right end of the graphic, reduce the exposure and shoot the same frame again.

Histogram vs dynamic range

As we have seen previously in this section, these are the dangers of having a histogram that touches one of the graph edges:

- If it touches the left edge or goes over it, the shadows are clipped.

- If it touches the right edge or goes over it, the highlights are blown out.

That means that when taking the picture, the camera hasn't been able to capture information about those tones, losing image quality. That is, the dynamic range of the scene does not "fit" into the dynamic range of the camera.

Let's see some examples of each of the 4 situations you can face, so you understand it better.

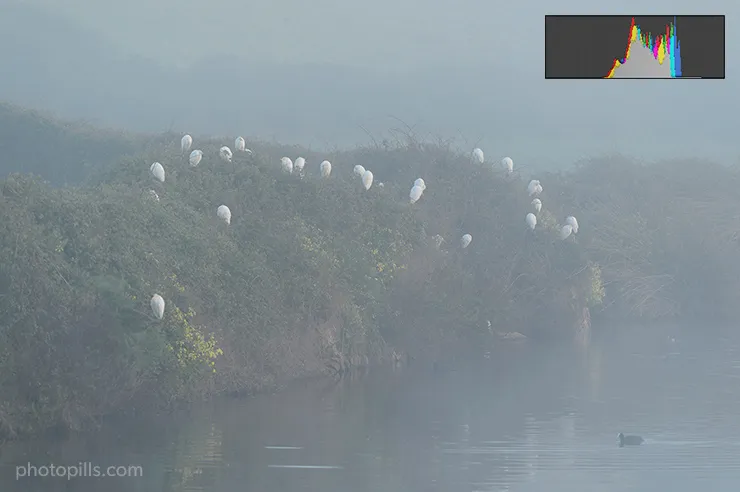

This picture's histogram is a clear representation of the image tonal balance. Look at the width of the graph. As you can see, shadows, midtones and highlights are represented from left to right.

Moreover, have a close look at the height of the graph and its "mountains". The higher they are, the more that tone has the picture.

In terms of dynamic range, this photo is perfect.

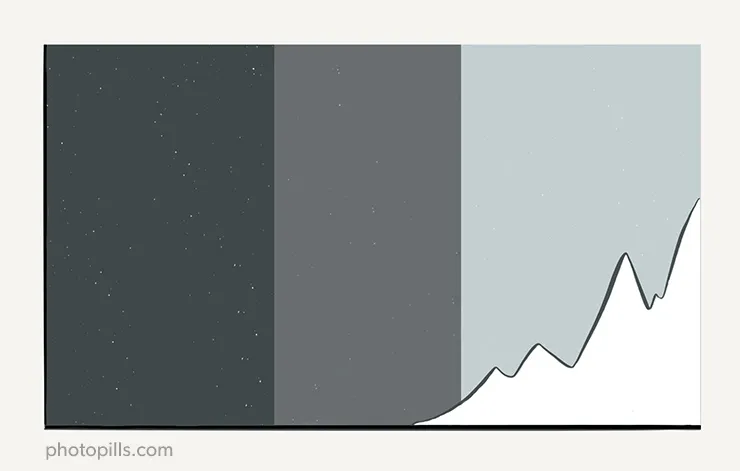

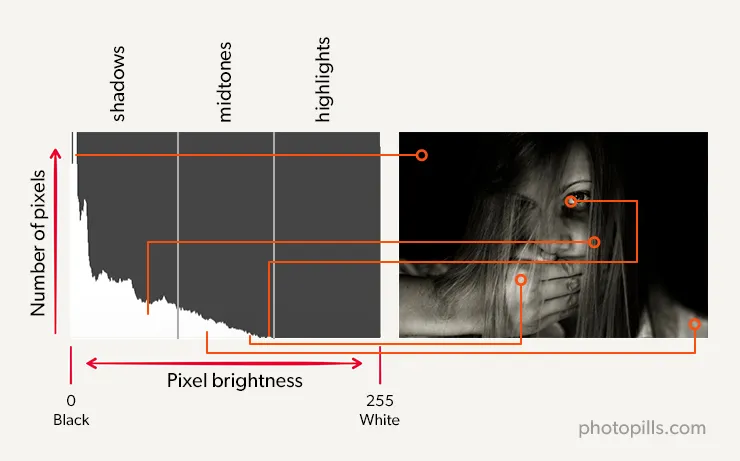

Here's a perfect example of clipped shadows. Look at the histogram.

Do you see the peak on the left side of the graph? It's completely out of the graph. This shows that in a large part of the shadows (the darkest area) all the information has been lost.

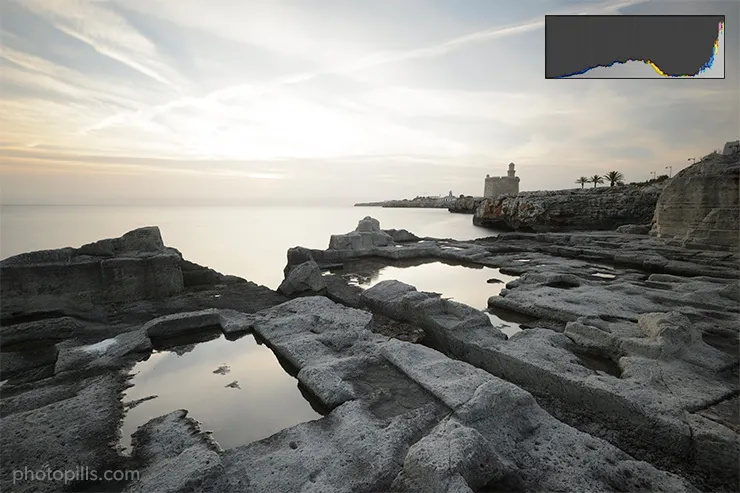

Conversely, look at the photo above. The histogram is almost flat, except at the far right end. Here you can clearly see that this part goes out of the graphic indicating that all the information has been lost in the brightest areas of the image.

Here's a weird example: the histogram is mostly flat except at the ends. And on top of it, at each end the histogram goes out of the graph.

So, although visually the photo doesn't strike you for being too dark or too bright, if you wanted to edit it it would be difficult to recover information from the highlights (almost all the sky and the chest of the puffins) and from the shadows (the back and the wings of the puffins).

Histogram vs tone

At the beginning of this section, I explained to you that the histogram graphically illustrates the distribution of captured tones in the image. More specifically, it shows you how many pixels each tone (or level of color intensity) has.

Therefore, by displaying the shadows (on the left side), midtones (in the center) and highlights (on the right) details, the histogram allows you to quickly see the tonal range or tonality of the picture.

In other words, depending on the main tone (dark, bright or medium), the detail of an image is focused on a certain area of the picture:

- Dark main tone, the detail is focused on the shadows.

- Bright main tone, the detail is focused on the highlights.

- Mid-main tone, the detail is focused on midtones.

The above image is a good example in which the main tone is intermediate. It's something that you can easily notice by looking at the colors displayed.

But you can also use the histogram to confirm it. In this case, most of the histogram is in the center of the graph. In fact, this "mountain" has a considerable height, indicating that the photo has a large number of midtones.

This photo, on the other hand, has a bright main tone. There is a lot of white, light grey... And if you take a look at the histogram you can observe that most of it is located in the right half. In addition, the peaks have a very narrow base showing the amount of bright tones in the image.

Without a doubt, here the main tone is dark. There are mostly shadows in the photo.

In addition, most of the histogram is in the left half of the graph. In fact, that "mountain" on the far left has a considerable height, indicating that the picture has a large number of dark tones.

What histogram should you look for when exposing?

It depends on the scene you have in front of you and how you want to show it.

Remember that the ideal histogram doesn't exist. If you're looking for a perfect histogram to use it as a base on your photos on, forget about it.

The histogram is nothing more than a representation of the tonal range of the scene and what you as a photographer want to convey. So, since there aren't two identical scenes or two photographers alike, nor there are two equal histograms!

Histogram vs contrast

In addition to the exposure, the histogram also gives you information about the contrast of your image.

Contrast is measured by the difference in brightness or tone between the brightest and darkest parts of the image.

If you notice wide differences, then your image has a high contrast. On the contrary, if you barely see differences your image is flat, without contrast.

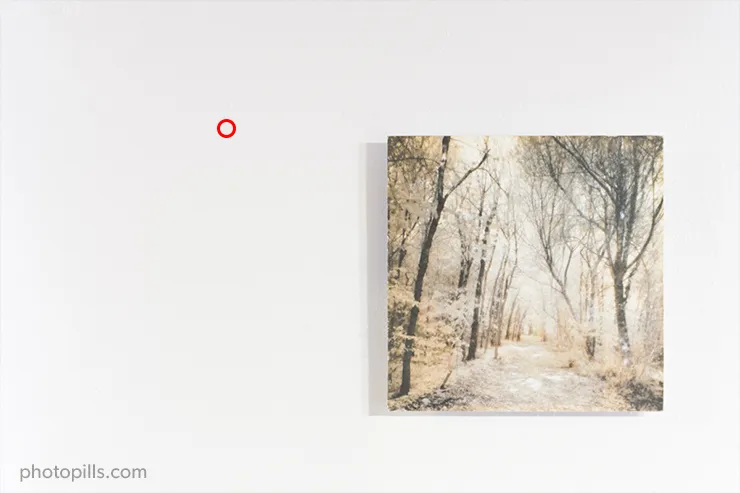

If there is little contrast in the scene the histogram is compressed (with a narrow base) towards the center. In contrast, if you have a lot of contrast, the histogram shows a larger graph and expands to the edges.

Look at the photo above. Don't you think it looks dull and flat?

That dullness or lack of contrast is very noticeable on the histogram. Or more precisely at the base of the histogram: it's very narrow.

Moreover, most of the tones are midtones, they are in the central area of the histogram. The "mountain" is in the center of the graph and it's very high in that specific area.

This photo shows the opposite because it has a high contrast. And you can see it on the histogram because it has a very large base with high peaks near the edges. It shows that there is a larger number of dark and bright tones.

The contrast depends on the type of light you have. For example, a photo taken during the golden hour, or on a cloudy or foggy day, will generally have little contrast due to the diffuse light present in the scene. On the contrary, a photo taken at noon with a hard light will have a high contrast.

Conclusion

Once you've taken the picture (or while you're shooting if you have a mirrorless camera), the histogram is the key tool you'll use. It will let you know if you've got the exposure you were looking for or not and, depending on this, if you need to adjust to the exposure triangle or not.

But, fortunately, before taking the photo, you can use two extra tools to get the right exposure: the camera's light meter and the handheld photometer.

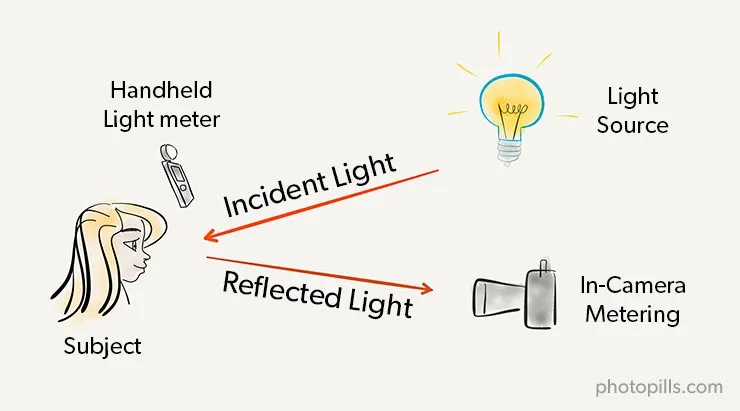

11.Your allies (the light meter and the handheld photometer)

You've learnt that to expose a photograph you have to decide the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings.

You also know that these three settings depend on the message you want to convey with your picture (depth of field or motion, for example, as you read in section 4) and the amount of light present in the scene (and its distribution as you have seen in section 10).

At this point, I can guess your next question:

"And how can I know how much light the scene has?"

To measure the light you need the help of two great allies: your camera's light meter and/or a handheld photometer.

What is the camera's light meter for

In photography, the light meter is a device built into your camera that uses a light meter to measure (or meter) the intensity of light in the scene. Thanks to it, the camera helps you determine the right exposure to take the picture.

In other words, the light meter helps you choose a combination of aperture, shutter speed and ISO that results in a properly exposed photo.

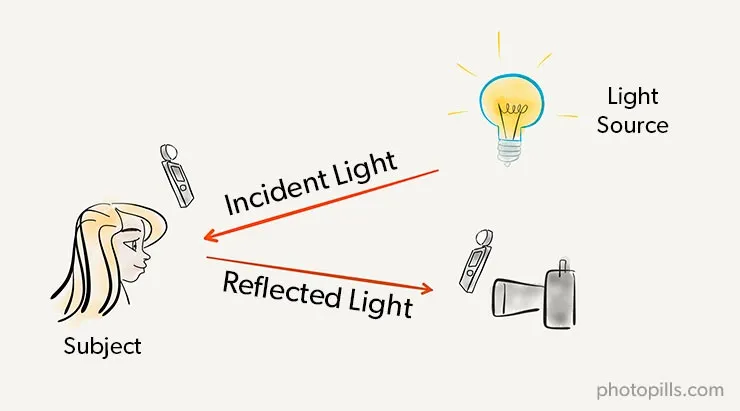

Don't forget that your camera's light meter is only able to meter reflected light, not the incident light present in the scene (section 2).

That is, it meters the amount of light that bounces back into the scene (not the one that hits it) and then enters through the camera lens. That's why it's called TTL (through the lens) light meter.

Sometimes you'll want to meter the incident light on a subject. In these cases, and as we'll see later, you'll need to use the hand-held photometer.

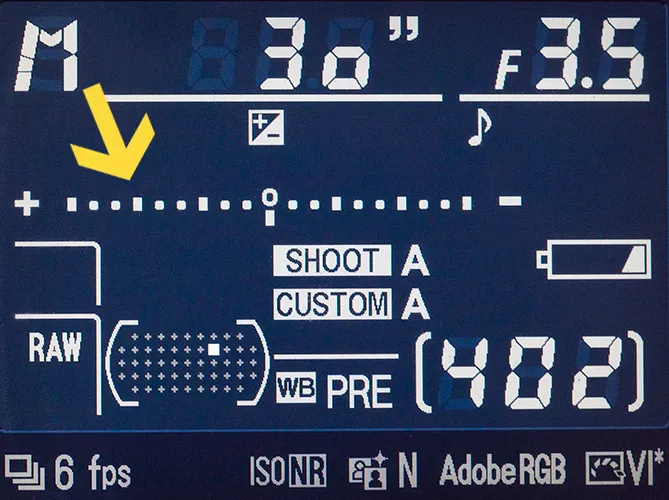

How the light meter works

Once you have metered the light (section 12) for a certain aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings, the camera's light meter tells you if you've got a correct exposure. But, it also tells you if you are over or underexposing your image, and in how many stops (or in fractions of a stop; don't forget that the most popular scale is the thirds of stop one).

Let's see what the light meter shows you on the camera LCD.

The combination of aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings that gives you a zero-centered light meter indicator zero allows you to capture a photo with an exposure that the light meter considers to be correct.

On the other hand, when the light meter moves to the right (+1, +2, etc.), you are overexposing the scene.

And when the light meter moves to the left (-1, -2, etc.), you are underexposing the scene.

In section 16 you'll find out that the light meter is not always accurate. Therefore, you will have to learn to interpret its values.

In section 18 I'll show you the different ways to choose a combination of aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings so that the exposure of your picture is always the one you're looking for (or the correct one).

What is the handheld photometer for

In addition to the camera's light meter, some photographers use an additional tool: the handheld photometer.

Compared to your camera's light meter, the handheld photometer allows you to meter the light more accurately.

This is because you can meter both the incident light, the one the subject you're capturing receives (if you place it next to the subject you want to photograph), and the light reflected in the scene (if you place it next to the camera).

And, because you can meter light more accurately, you have more control over your pictures' exposure.

In practice, you usually use the hand-held photometer in situations where you plan to use artificial lighting, such as in a studio. But in the vast majority of cases, your camera's light meter will be more than enough.

How to meter light

Great!

Now you know that you can use the light meter to meter the light intensity of the scene so you can expose your pictures... But how does it meter it?

Light is obviously distributed unevenly in the scene. There are brighter and darker areas.

So how do you meter the light to calculate the exposure?

You'll find the answer in the next section ;)

12.Your camera's light metering modes

It's logical!

To know if the amount of light captured by the sensor when taking the picture is appropriate, you have to tell the camera what the light intensity of the scene is.

Yes, the light meter meters the light intensity...

But, usually, the scene is illuminated with different intensities (brighter, darker lights). So you have to tell the camera how to meter the intensity of light in the scene.

Do you want to meter the brightest tones? The darkest? Or use the average intensity of the scene?

What's obvious is that the tone on which you meter the light is correctly exposed. You'll capture all the detail in the elements of the scene that has that tone.

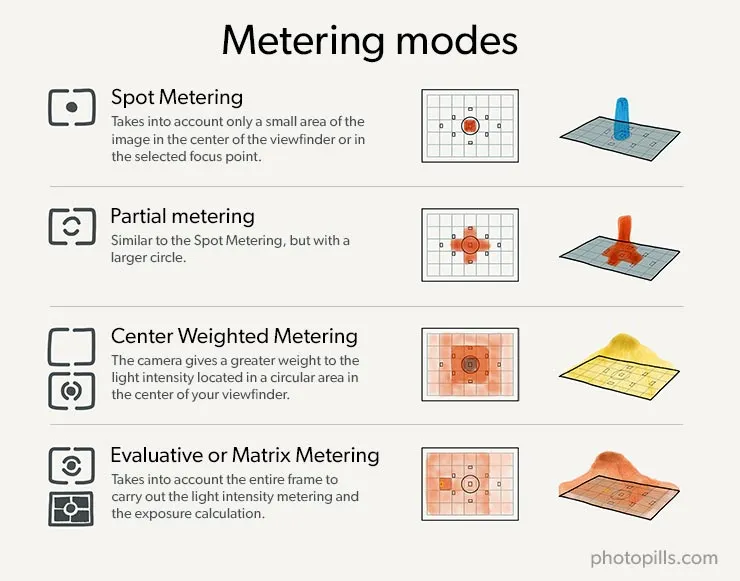

How and where you meter the light depends on the scene and what you want to get it in the photo. Sometimes you'll be interested in metering light on a single point (spot metering). Other times, you will want to use an average of the different light intensities of the scene (matrix or evaluative metering).

So you should choose the light metering system to calculate the exposure that suits you in each situation.

That is, depending on the tone distribution in the scene, use the metering method that allows you to correctly meter the tone intensity of the areas you want to capture in detail (expose correctly).

Fortunately, in order to accurately expose different light situations, cameras generally allow three (or four) different metering modes:

- Matrix (or evaluative) metering.

- Center-weighted average metering.

- Spot metering.

- And in some models, the partial metering.

Each of these methods works by assigning a relative weight to each of the areas of the image. Thus, heavier areas will be considered more credible and contribute more to the final calculation of exposure.

Take your camera's user manual and discover how to set up the metering method... It's essential!

Matrix or evaluative metering

The matrix or evaluative metering takes into account the entire image (i.e. what is within the frame) to carry out the light intensity metering and the exposure calculation.

How to meter the light and calculate the exposure

The camera divides the image into several zones and analyzes the existing tones in each of them, giving greater weight to the area surrounding your focus point.

Finally, it establishes an average of the light intensities and calculates the correct exposure, also taking into account other variables like the scene color or the distance to the subject.

This type of metering is usually the default metering of all current DSLR and mirrorless cameras because it's the easiest to use.

When you should use it

The matrix method is ideal for scenes with very little contrast (similar tonalities), as the calculated intensities mean is similar to the different intensities or tones present in the scene. All in all, you are telling the camera that the light in the scene is homogeneous (very similar).

When you shouldn't use it

Unfortunately, this system has a flaw. The camera won't be able to solve certain scenes with high contrasts, so you won't always get the result you are looking for.

Look at the photo below carefully.

Tell me, what do you think about its exposure? Is it correct?

If your answer is "yes", I have no choice but to correct you...

In general, the photo is dark. That is, underexposed.

Look closely at the people, don't you see they are dark? The main source of light (the Sun) comes from the right and is quite close to the horizon (the shadows in the bottom left corner are very long).

Let me use another example. Imagine that you are at a concert of your favorite group. Surely at some point in the show the singer is illuminated by a beam of light and the rest of the band and the stage remain in total darkness. And that's exactly the moment you want to capture.

If you leave your camera in matrix metering mode, the internal light meter will mess up. Try to compensate for the areas of maximum brightness (the singer illuminated by the spotlight) with the zones of maximum darkness (the rest of the scene) to establish an average.

You take the picture and... Epic fail! :P

Center-weighted average metering

With the center-weighted average metering, the camera gives a greater weight to the light intensity located in a circular area in the center of your frame.

How to meter the light and calculate the exposure

The size of this circular area depends on the camera manufacturer. And on some models, you can even set it. When metering, all the areas outside this circular area also count, despite having a very small weight.

Unlike matrix metering, your camera doesn't take the focus point into account. It always gives priority to the central area of your frame.

When you should use it

This metering method is useful when you want to photograph a subject that has a high contrast compared to the background because it allows you to meter the light of that particular subject.

At the same time, as the camera takes into account the rest of the areas of the frame, it allows you to include them giving some exposure (light).

Thus, you have your subject perfectly exposed and framed in it environment.

For example, pay attention to the photo below.

As you can see, the emphasis of the exposure (and focus) is on the conductor. He's almost in the center of the composition, he's the person who receives more light and the one that is perfectly exposed.

Simultaneously, the rest of the musicians are slightly underexposed in such a way that they are part of the scene, you look at them, but they're not the main focus.

Your attention is focused on the conductor although the other people provide enough context for you to know where he is and what's happening around him.

Here's another example where the center-weighted average metering is extremely useful: the portrait.

Here your intention is to highlight your subject. She's in the center of the image so that the spectator ignores everything else.

The center-weighted average metering gives more importance to the center of the frame. In other words, the outside area has hardly any impact on the exposure calculation.

Therefore, in your portrait the person's face is correctly exposed. It doesn't matter if the background looks a little brighter or darker than how it is on the scene. Your intention is to isolate your foreground from the background.

When you shouldn't use it

The big drawback with respect to the matrix metering is that it isn't as automatic. As a photographer, you have to tell the camera where to meter the light. In addition, you have to recompose the scene once the camera has metered the exposure.

Therefore, if you can apply the matrix metering, try to avoid the center-weighted average metering.

At the same time, it's not really useful if you are in front of a high contrast scene. In this case, the important thing is to meter the light that predominates in the scene (or to which you want to give more importance). Here the most appropriate metering mode is the spot one.

Spot metering

The spot metering takes into account only a small area of the image (in the center of the frame or in the selected focus point) to carry out the exposure calculation.

How to meter the light and calculate the exposure

In the spot metering your camera only takes into account a very small circular area. And unlike center-weighted average metering, this metering point can be placed either in the center or in any of the focus points of your camera.

This allows you to choose precisely where to meter the light.

This restricted metering system allows you to decide exactly what composition point you want to use to calculate the exposure.

Therefore, in scenes where there is a very bright or very dark element in the composition, but it's not your main subject, it's best if you use this metering mode. That way you expose your subject correctly without other elements within the frame altering the metering.

When you should use it

As I said, it's extremely useful for high-contrast scenes, such as a scene where your subject is much darker or brighter than the rest of the frame.

In the backlit portrait you have below, you have to meter the light on the face of your subject (the child who is looking at the camera) and avoid keeping only his silhouette.

In fact, because I deliberately chose to expose correctly the kid's face, the upper body of the other child and the windows are overexposed (much clearer and brighter than they should).

Another example: you want to capture detail of the surface of the Moon in the middle of the night. Thanks to the spot metering you can measure exactly the light of the Moon and avoid capturing it like a white circle. That's how it would look if you used the matrix metering.

Many photographers use this metering mode by default as it allows you to control the exposure as much as possible.

But the truth is that, like many other decisions in photography, it's best to experiment and see what you like (or what's better) in each situation.

When you shouldn't use it

Actually, there is no particular scene where you don't want to use this metering mode.

As I told you before, this is the most precise metering mode so it's useful in any scene.

Partial metering

This metering mode is very similar to the spot one, but with a larger circle. So you can use it pretty much in the same way, even though you use a larger area of the scene to carry out the metering.

This metering mode isn't available on all cameras. Depending on the brand and model of the camera, you may or may not have it.

When you should use it

Taking into account that this metering mode is very similar to the spot metering mode, you can use it in the same way and in similar scenes.

That is, in high contrast scenes or scenes in which your subject is much darker or brighter than the rest of the scene.

When you shouldn't use it

Don't use it if you want to make a more generic metering because your scene is lit up homogeneously.

Same thing if you want a very precise metering. In that case, it's better to use the spot metering.

Conclusion

Depending on the scene and the result you are looking for, use a different metering mode.

Once you have decided the mode and you've metered in the right place, you only need to determine the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings, take the photo and review the exposure using the histogram.

Therefore, it's time to analyze the different systems you have to determine the exposure triangle settings.

Let's have a look at the different exposure modes of the camera.

13.Your camera's exposure modes

When you choose the exposure mode of your camera, you're determining who (you or the camera) will decide the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings.

You can choose among the following exposure modes:

- Automatic, if you want your camera to have absolute control of the three variables.

- Manual, if you want to be the one who decides the exposure triangle value.

- Or some of the semi-automatic modes when you want to set one of the settings and let the camera decide the other two.

You can choose the exposure mode directly in the exposure selector of your camera.

Don't confuse the exposure modes with the metering modes

Don't mess them up!

The exposure modes have nothing to do with the metering modes I just explained in the previous section.

The metering modes allow you to tell your camera what method to use when metering the light of the scene. Instead, exposure modes let you tell your camera how to choose the aperture, shutter speed, and ISO settings.

In other words, you can consider each exposure mode of your camera as a shooting mode. That is why sometimes you say you shot in automatic, in manual, etc.

Let's see how does each one of them works and how you can use them to expose your photographs.

Let's dive in!

Automatic mode (Auto)

When you use a camera for the first time it's the easiest way to quickly start taking pictures like crazy.

In fact, many photographers never use the other exposure modes, wasting the great creative potential that the camera offers them.

How it works

The camera does it all for you. You just have to worry about framing and pressing the shutter release button.

It determines the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings to get the correct exposure. That is, having the light meter centered (indicator on the zero). It even takes care of choosing the metering mode.

In addition, the camera also activates its flash if it considers that there is not enough light in the scene you are capturing.

Everything seems so simple!

However, you'll soon discover that you have no control over your camera settings. Since it's the camera that makes all the decisions for you, you lose a lot of (or almost everything) your creative power.

When you should use it

Like everything in life, you learn step by step, practicing. Usually, if you are starting out in photography, it's the first exposure mode you use before taking the next step.

And if you keep improving, you'll realize that there are many pictures you can't take. Since you're unable to control the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings as you want, you'll notice that your creativity is very limited:

- You don't control the depth of field to guide the spectator's attention.

- You don't control the movement (freezing it or not).

- You don't control the exposure.

- You don't control the light.

- You don't have any control on your image.

In fact, I recommend you abandoning the automatic exposure mode as soon as possible. It's the only way to become a photographer.

When you shouldn't use it

Most photographers who take photography seriously never use the automatic mode.

As a photographer you'll want to make the most out of your gear to tell different stories. And, for this, you'll have to use the semi-automatic and manual exposure modes.

In short, no matter what type of photo you want to take, the automatic mode limits you.

Scene modes

In addition to the automatic mode, the vast majority of cameras allow you to choose an exposure mode depending on the different scenes you face.

The scene modes tell the camera what kind of picture you have in mind, so that it makes the adjustments allowing you to get that photo.

How it works

Depending on the selected scene mode, your camera automatically decides the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings so that the light meter is centered (indicator on the zero).

Here are some scene modes:

- Action or sport: Your camera chooses a fast shutter speed in order to freeze motion. If necessary, it also increases ISO to get a proper exposure.

- Landscape: Your camera selects narrow apertures to increase the depth of field.

- Portrait: Your camera uses wide apertures to a get a shallow depth of field and a blurred background behind the subject.

- No flash: Your camera turns off the flash and tries to get the right exposure without having to use it.

- Night portrait: Your camera sets a slower shutter speed than in portrait mode to capture detail from the background. At the same time, it automatically activates the flash to illuminate the subject.

- Macro: Your camera tries to close the diaphragm as much as it can to increase the depth of field.

When you should use it

When you face a scene in which you need to quickly change the shooting mode and you don't have time to change the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings.

These modes are kind of a shortcut.

Also, you can use a "wrong" mode to get the effect you are looking for. The fact that a scene mode has a specific purpose doesn't mean you can't use it in a different situation, and thus get a different result.

Let me give you some examples so you get it.

If you want to photograph a sport scene, use the portrait mode.

"What are you talking about Toni? The portrait mode? Seriously?"

Of course. In this case the camera uses a large aperture so it's forced to use a fast shutter speed. And this is exactly what you need to freeze the action or a quick movement.

Magic! ;)

Another example.

Use the night portrait mode even if your scene is illuminated or when you're indoors. This way you are using the flash as a fill taking into account the ambient light the scene has. Thus, both help you get a better exposure.

And the last one (although I could give you many more).

If your camera has it and even if it's not New Year's Eve, use the fireworks mode to create long exposures in which you convey motion. In this case, the camera uses a slow shutter speed so some parts of your image will be blurred, like water or a moving vehicle.

When you shouldn't use it

In general, scene modes are very limited and can be useful if you are a beginner and want to experiment with them.

A good exercise is to try several of them in the same scene and analyze the different results you get. Look how the photo looks like and try to understand why it turned out that way.

Is the background out of focus? It's probably due to a big aperture because this causes a shallow depth of field.

Is the photo too bright (overexposed)? It may be because the shutter speed is too slow: light has reached the sensor for too long.

As soon as you have an idea of what each scene mode does, stop using them.

It's time for you to decide.

Program mode (P)

It's a similar mode to the automatic one. The big difference is that it gives you a little bit more freedom when deciding the exposure triangle settings.

How it works

In this case, your camera automatically chooses a combination of aperture and shutter speed settings to get the right exposure (zero-centered light meter).

However, it doesn't automatically trigger the flash or modify the ISO. In this case, you can change the ISO manually if you see fit.

You can also select the metering mode, use the exposure compensation (±EV), change the white balance and some other functions.

How to change the aperture and shutter speed while maintaining the exposure

The P mode has a rather peculiar functionality called Program Shift or Program Flexible (P* or Ps).

This shooting mode allows you to change the aperture and shutter speed settings combination while keeping the same exposure.

To use the Program Flexible, you only have to press the shutter release button halfway and turn the selection dial on your camera.

Let's look at an example.

Imagine you're at the beach and you want to take a picture of the landscape that surrounds you. You have your camera in P mode.

When you press the shutter release button halfway, the camera tells you that an aperture of f/8 and a shutter speed of 1/125s allows you to get the right exposure for that specific scene. Turn the selection wheel. Now the camera provides you an aperture of f/11 and a shutter speed of 1/60s as an alternative, always keeping the same exposure.

This allows you to have more control over the effect you want your final image to have.

Therefore, if you're looking to blur the background, you can select a combination where the aperture is larger. However, if you want to freeze the motion, you can select a combination in which the shutter speed is faster.

But there is a drawback!

The camera doesn't let you choose the aperture and shutter speed separately. You must use the settings that the camera considers to be "correct".

In order to have a greater control over the exposure, you have an ace up the sleeve. You can compensate the exposure (section 14).

When compensating the exposure, you are telling the camera to overexpose or underexpose the image to a certain number of exposure values or EV (section 8).

When you should use it

The P mode is very useful if you're a beginner photographer. It helps you understand the relationship between aperture and shutter speed.

Regardless of your photographic level, the P mode is very useful in street photography.

In this genre of photography, composition and speed are essential. That's why, when you're walking down the street and several things happen at the same time, you only have a few seconds to compose and shoot. Actually, in most cases, you don't have time to think about the settings you need to expose correctly, or to set them!

So here the P mode (or the P* alternative) comes handy. Let the camera find out the shooting settings for you and take care of two essential things: composing and focusing.

When you shouldn't use it

In general, and as I said, this mode is automatic. Too automatic. And this limits your creative power.

Forget about taking photos of the Milky Way, long exposures, a sports event (and an endless list of other types of image) in P mode.

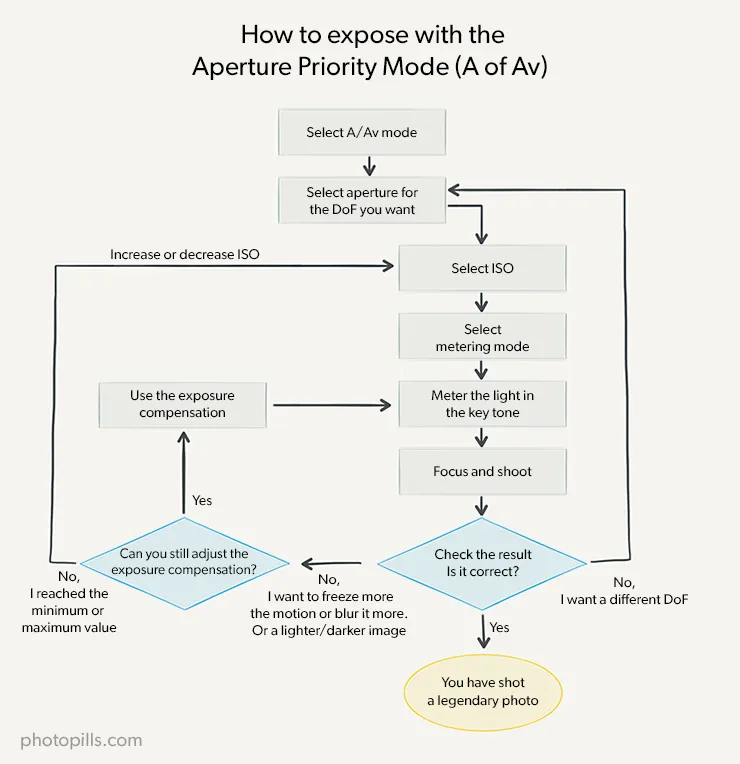

Aperture Priority mode (A or Av)

This is one of two semi-automatic modes that all DSLR and mirrorless cameras on the market have.

"Toni, what's this "semi" thing?"

Basically, semi-automatic modes allow you to freely choose the aperture or the shutter speed settings. One or the other. This gives you partial control over the exposure settings.

At the same time, your camera helps you achieve a correct exposure by adjusting the other two parameters of the exposure triangle so that the light meter is centered (indicator on the zero).

How it works

In Aperture Priority mode, you can choose the aperture, as the name implies.

Once you've selected the aperture you want, your camera automatically selects the shutter speed that results in a well-exposed photo (the light meter is centered at zero), taking into account the configured exposure mode.

As for the ISO, you can set it manually or leave it in automatic. If you decide to leave it in automatic, I recommend that you set a range of ISO values as I explained in section 5.

Usually the range goes from the native ISO (100 or 200) and the maximum ISO at which the camera doesn't produce a lot of noise (800, 1600, 3200, depending on your camera's performance).

It's a way to keep the noise under control.

What it is for

"And what do I get by controlling the aperture?"

To determine the depth of field.

I already did a brief introduction of how useful it is in section 4. But if you want to become a master I suggest you read our photography guide to depth of field (DoF).

If you read this guide, you'll acquire the superpower to decide which part of the photo you want perfectly focused and which part you want to be completely out of focus, and thus tell the story that you have in mind.

Remember that thanks to the depth of field you can get:

- Sharp photos from the foreground to infinity.

- Or leave certain areas of the image out of focus on purpose to lead the spectator to a specific subject or point.

In short, use the Aperture Priority mode (A or Av) to control the depth of field your photo will have.

How can you blur the background?

If you want to blur the background to enhance your subject only, for example when you want to make a portrait, use a wide aperture. For instance, set an aperture of f/1.4, f/2.8 or f/3.5, depending on the lens you are using.

Once it's set, focus on your subject and take the picture. Your camera automatically decides the shutter speed so that the photo is correctly exposed (zero-centered light meter) based on:

- The light available in the scene.

- And the metering mode that you've selected.

It will most likely be a fast shutter speed to compensate for the large diaphragm aperture. However, keep in mind that this will depend entirely on the light of the scene.

The camera may indicate that you can't get a correct exposure (usually with the "Hi" indicator) because you don't have a shutter speed fast enough to expose correctly.

In this situation, you must reduce the amount of light the sensor is capturing. In order to do this, you have several options:

- Bring down the ISO.

- Use a narrower aperture.

- Or use a neutral density filter (ND) to reduce the amount of light reaching the sensor.

How can you get everything focused?

If you do landscape photography or astrophotography (a type of night photography), you generally try to maximize the depth of field so that everything is perfectly focused.

How can you get it?

It depends on the focal length you use.

If you use a wide angle lens, that is a short focal length (14mm, 18mm, etc.), and regardless of the aperture you want to use, the easiest is to focus at the hyperfocal distance and forget about everything else.

You can learn how to do it in less than 1min watching the following video.

If you use longer focal lengths (70mm, 200mm, 500mm) instead, choose a relatively narrow aperture, f/8 or f/11 for example, and focus on a point located in the lower third of the scene.

In this case, as you close the aperture, your camera will obviously determine a slower shutter speed. Keep in mind that the diaphragm is allowing less light through it so the camera compensates it with a slower shutter speed.

The problem now is that depending on the shutter speed determined by the camera, you'll have use a tripod. If you don't, your photo will be blurred unless you have an extremely steady hand.

On the other hand, the camera may indicate that you can't get a correct exposure (usually with the "Lo" indicator) because you don't have a shutter speed slow enough to expose correctly.

Remember that for shutter speeds over 30s, you must use the Bulb mode of your camera. That means using the camera in Manual exposure mode (M).

To increase the amount of light captured by the sensor, you have two solutions:

- Select a wider aperture, getting a shallower depth of field.

- Or set a higher ISO to increase the amount of light reaching the sensor (but be careful with the noise!).

If your goal isn't to maximize the depth of field, but to increase it, use smaller apertures (f/8, f/11, etc.).

Don't forget motion

Remember that it's the camera that sets the shutter speed and not you. So you should examine whether the motion you've got in the final image is what you want or not (freeze motion or not).

When you should use it

The Aperture Priority mode is very versatile and is useful in most situations.

Let's look at some examples.

Imagine a situation where the light is good or the day is sunny. When the light is relatively steady, the risk of blurring your photos is minimal: the shutter speed is always going to be fast enough to capture motion.

What's more, the "Sunny f/16" rule that I'll explain in section 19 establishes that when there is a lot of Sun it's best to shoot at a small aperture (at f/16). And the truth is that it works. So the best thing you can do is to focus on determining the depth of field you want or use a small aperture to focus on everything in your frame.

In this sense, this also applies to a portrait. Ask yourself what you want to get:

- A huge blur to make the background completely out of focus?

- Your subject's face incredibly sharp?

Finally, these questions are also useful when capturing a landscape during the day. Your aperture determines if you want the whole landscape in your frame to be focused or not.

When you shouldn't use it

As I said, this mode is very versatile so there are few situations in which you can't use it.

Perhaps the two most common ones are the following.

On the one hand, a scene where there is a constant action.

For example, in sports photography (if you attend a school event) the important thing is to freeze motion, to see the faces of the players and what they were doing at that moment (kicking a ball, throwing a basket, etc.). In this case, it's essential to control the shutter speed, the depth of field is not the key factor.

On the other hand, a scene in which there is no light, at night for example. If you practice night photography, you have to set the aperture, but you can't rely on you camera to set the shutter speed and ISO settings in order to get the right exposure.

It's, without a doubt, a demanding type of photography that requires you to shoot in Manual mode (M).

Tips

- Please note that depending on the metering mode you have selected (evaluative, center-weighted average, spot), the photo may be underexposed or overexposed.

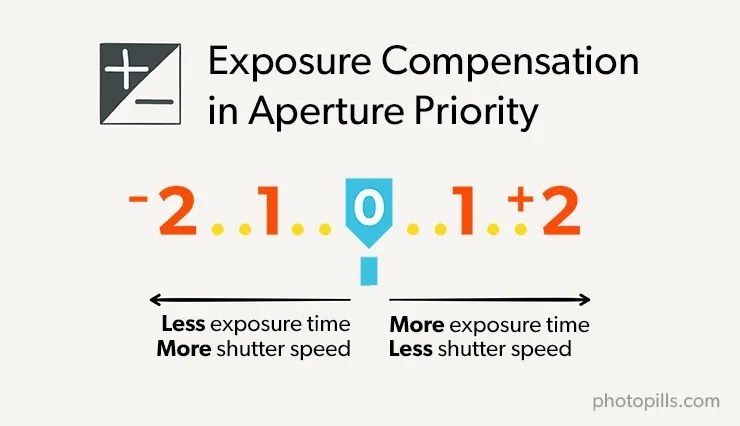

- Remember that you can always use the exposure compensation button (± EV) of your camera (section 14) to make the necessary adjustments so that the histogram is balanced. With this setting you force your camera to use a slower shutter speed (avoid underexposure) or faster (avoid overexposure) than the one it has initially set.

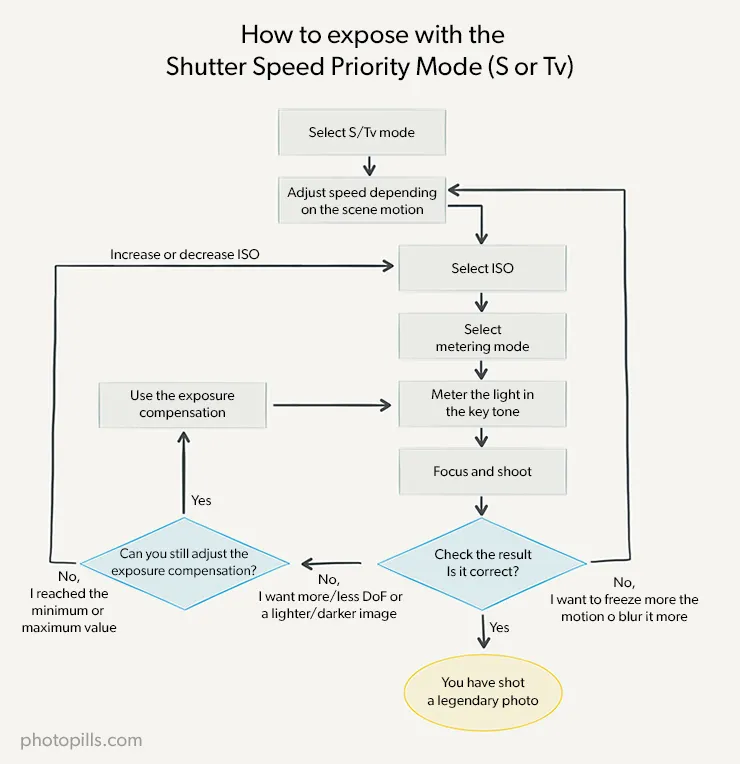

Shutter Speed Priority mode (S or Tv)

This is the other semi-automatic mode that all the DSLR and mirrorless cameras on the market have.

How it works

In this particular mode, you can choose the shutter speed.

Once you have selected the shutter speed you want, your camera automatically selects a diaphragm aperture that results in a well-exposed photo (zero-centered light meter).

As with the Aperture Priority mode, you can manually choose the ISO or leave it in automatic.

What it is for

"And what do I get by controlling the shutter speed?"

To freeze motion or, on the contrary, leave blurry areas of the image to convey this motion.

In short, you use the Shutter Speed Priority mode (S or Tv) to control how the motion is reflected in your picture.

You can freeze it, if you photograph a racing car at full speed or a bird in flight. Or you can blur a subject, creating a silk effect in a waterfall or capturing the trail of a few clouds as they move.

How can you freeze a moving subject?

Easy peasy!

Simply select a fast shutter speed. In section 4 you have many examples of shutter speeds for a multitude of different scenes.

For example, suppose you want to freeze a moving race car. To achieve this, use a speed of 1/1000s or 1/2000s and let the camera choose an aperture to get the correct exposure.

It will certainly set a wide aperture to compensate for the fast shutter speed so that you can expose the image correctly.

However, your lens may not have a aperture large enough to get a correct exposure.

If this happens, you can choose between two solutions:

- Use a longer exposure time without, perhaps, freezing any motion.

- Or crank up the ISO (but be careful with the noise!).

How can you blur a moving subject?

If you want to indicate that there is motion by showing silky water or blurring a subject, select a slower shutter speed.

How slow?

The amount of time depends on you. But after a second the effect will be stronger.

Obviously when you select a slower shutter speed, the camera automatically chooses a narrow aperture to try to reduce the amount of light captured, thus exposing the picture correctly.

What if your camera can't close the diaphragm enough to get a correct exposure?

Once again, you have three alternatives:

- Use a faster shutter speed.

- Reduce the ISO (if you're not using the native ISO).

- Or use a neutral density filter (ND) to reduce the amount of light reaching the sensor.

Don't forget the depth of field

Bear in mind that depending on the shutter speed you choose, your camera will select a certain aperture. And this decision of the camera will affect your picture's depth of field.

When you should use it

In the previous section, I told you that it is better not to use the Aperture Priority mode (A or Av) when you are in a situation where there is action around you and you want to freeze the motion.

And I gave you the example of a sports competition.

Here is when you have to use the S (or Tv) mode!

Because that's exactly what you want: control the time the sensor receives light in order to freeze the action you have in front of you.

When you shouldn't use it

When it's better to use the Priority to Aperture mode (A or Av)... :P

That is, when you want to have great control over the depth of field or when you need to make sure the sensor captures plenty of light.

In fact, both modes are complementary: when one of them is useful, you shouldn't be using the other one and vice versa.

Tips

- When you shoot handheld, without a tripod, the picture may be blurred. To avoid this use a shutter speed of at least 1 divided by the lens effective focal length (1/effective focal).For example, if you use a full frame sensor camera, with a 50mm focal length lens, you can use a shutter speed of up to 1/50s. With a focal length of 100mm, the minimum shutter speed is 1/100s.Furthermore, I recommend you using a shutter speed shorter than that. For example, when shooting with a 50mm focal length use a shutter speed of 1/60s. Or a shutter speed of 1/250s with a 200mm focal length.If you have a camera with a crop factor (1.5x for example) with a lens at a focal length of 50mm, the minimum shutter speed is 1/(50×1.5) = 1/75s. In this case, you must use the effective focal length (focal length×crop factor of your sensor).

- Don't forget that if the lens or camera has a vibration reduction system you can use 1 or 2 stops slower shutter speeds, or even more. Unfortunately, if your pulse is not very good, your pictures may be blurred. With slow shutter speeds, the easy way is to use a good tripod. With a sturdy tripod, you don't need to use the vibration reduction system.

- As with the Aperture Priority mode (A or Av), depending on the metering mode you have selected (evaluative, center-weighted average, spot), the picture may be underexposed or overexposed.

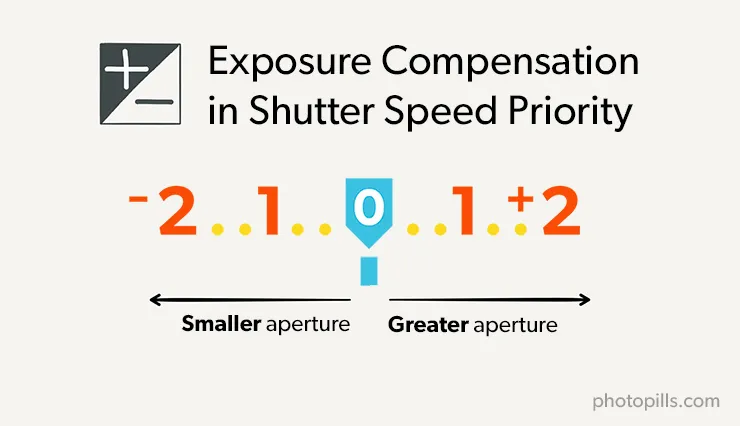

- Remember that you can always use the exposure compensation button (±EV) of your camera (section 14) to make the necessary adjustments so that the histogram is balanced. With this setting you force your camera to use a wider (avoid underexposure) or narrower (avoid overexposure) aperture than the one it has initially set.

Manual mode (M)

This is the mode of the bravest ones! No more automatisms!

With the Manual (M) mode you have absolute control over exposure and other photographic effects (depth of field, motion) to get the picture you crave.

All responsibility lies with your hands.

How it works

There are many situations in which your camera is wrong or can not automatically set some of the exposure triangle values you need to get a particular photo.

For example, in night photography the camera is unable to help you expose because there is hardly any light (it's pitch black).

With the Manual mode (M), you are the one that chooses the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings to get the result you are looking for.

Hard?

Don't feel hopeless. You're not alone.

You can count on two great allies that will make your life much easier when working on your exposure: the light meter and the histogram.

The important thing is to capture the photo you have in your head and know how to decide the settings. After carrying out a few tests (trial and error photos), you can't fail.

In section 24 you'll find many examples of how to expose explained step by step.

First the idea, then the technique

Before deciding the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings, determine the photo you want and what limitations you have:

- Do you want a shallow depth of field or not?

- Is there any motion in the scene? Do you want to freeze the motion or not?

- Is there too much or too little light available?

For example, in wildlife photography, if you want to capture the movement of a bird in flight, you must use fast shutter speeds. This forces you to use larger apertures and high ISOs when exposing.

In addition to this, since you can't approach the animal, you have to use long focal lengths (400mm, 500mm).

This, along with the large apertures, results in a shallow depth of field in the image. So you have to make sure to make it right when you focus on the bird.

Another example. If you want to photograph the Milky Way, I don't think you want to capture Star Trails, so use a fast shutter speed (calculate it with the PhotoPills Spot Stars calculator, either with the NPF rule rule or the 500 rule).

In order to capture the maximum number of stars and expose the image correctly, you have to use very large apertures (f/2.8) and high ISOs (1600, 3200, 6400, depending on how your camera's noise performance).

In this case, when using short focal lengths (14mm, 18mm), you can focus at the hyperfocal distance to maximize depth of field and thus have in focus everything from the foreground to the stars.

In short, depending on the photo you are looking for, the logic when choosing aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings will be different.

In section 18 I'll explain you how to choose the exposure triangle values to get the result you're looking for, both in terms of the desired effect and the desired (correct) exposure.

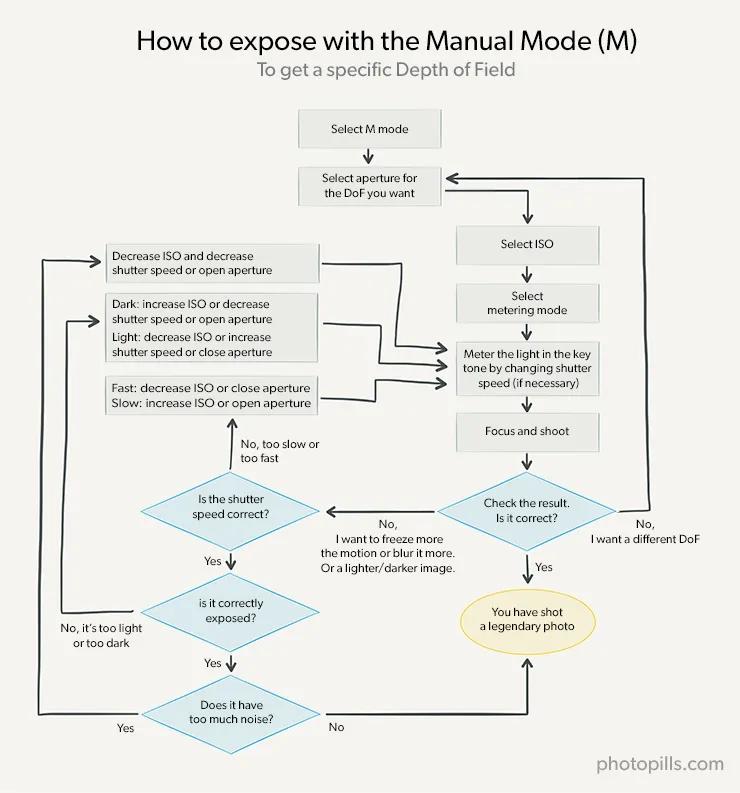

How to expose when you are looking for a certain depth of field

If you are looking for a specific depth of field, your first step is to choose the right aperture.

- Do you want a shallow depth of field? Select a big aperture (small f number, for example f/2.8 or f/3.5).

- Do you want a greater depth of field? Select a small aperture (big f number, for example f/8 or f/11).

- Do you want to maximize the depth of field?

- If you use a short focal length (14mm, 18mm), focus at the hyperfocal distance regardless of aperture. In this case, the depth of field criterion is not critical when choosing the aperture so you have more freedom to set the shutter speed.

- If you use a long focal length (200mm, 500mm), select a small aperture (big f number, for example f/8 or f/11).

Once you've set the aperture, your next step is to determine which shutter speed and ISO results in the exposure you're looking for.

Moreover, when setting the ISO use values that don't cause a lot of noise in the image (keep it as low as the scene allows it).

How do you determine the exposure?

If you have a DSLR camera, you'll have no choice but to go for the "try and fail" strategy.

So meter the light and set the three parameters in this order, aperture, shutter speed and ISO, to get the exposure you want. A good starting point is to set the parameters so that the light meter is centered at zero.

Then, take the picture and check the result on the LCD and the histogram.

If you got the exposure you were looking for, great!

Otherwise, change the shutter speed (or the ISO) accordingly. Decrease the shutter speed (or increase the ISO) if the picture is underexposed or increase it (Or lower the ISO) if the image is overexposed.

Take another picture and look at the LCD and histogram again. If it's still not what you are looking for, keep changing the shutter speed (or the ISO)...

And so on until you hit the nail on the head.

It may seem complicated at first but, with the practice you'll get facing different shooting situations, you'll know exactly which parameters to change first, and its settings to quickly get the right exposure.

What I want now is that you begin to understand the logic that you should apply when exposing and taking a picture. In section 18, you'll find a much more detailed explanation.

Finally, if you have a mirrorless camera, the electronic viewfinder makes your life much easier. You'll see on the screen how the exposure varies as you change the shutter speed and the ISO.

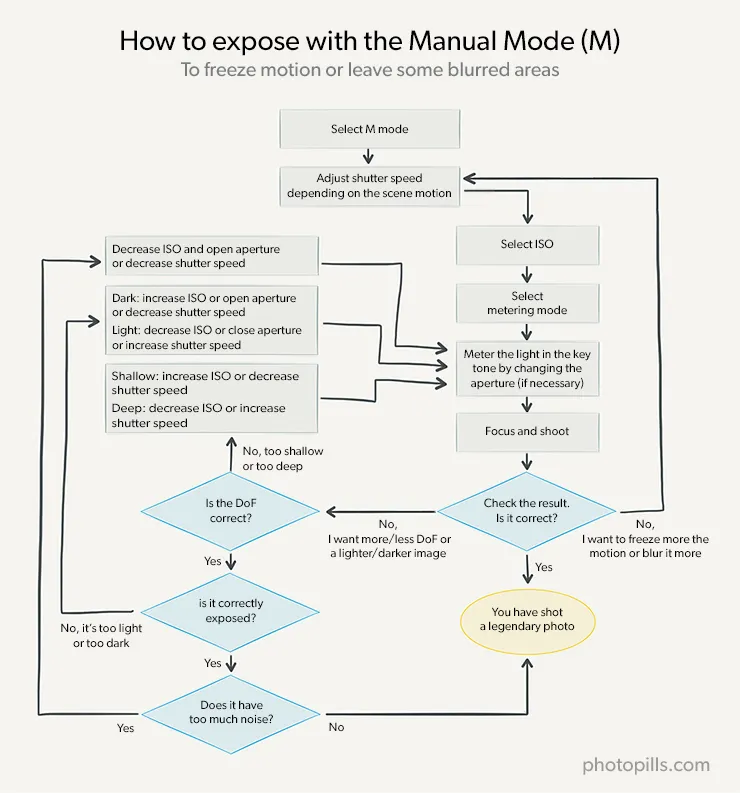

How to expose when you seek to freeze motion or not

If you are looking to play with motion blur, your first step is to choose the right shutter speed.

- Do you want to freeze motion? Set a fast shutter speed (for example 1/2000s).

- Do you want to have some blurry elements or trails? Set a slow shutter speed (for example 1/4s, 1s, 5s, etc.).

In section 4 you'll find many examples of shutter speed values that I suggest you according to the scene you want to photograph.

Now, the second step is to determine which aperture and ISO results in the exposure you're looking for.

Do you remember the method I just explained in the previous section (the depth of field one)?

You surely do.

Well the procedure is the same:

- If you have a DSLR, you'll have to use the "try and fail" strategy.

- If you have a mirrorless camera, everything will be much easier thanks to the electronic viewfinder.

Alternative mode: combining the semi-automatic modes (A or Av, S or Tv) or Manual (M) with the automatic ISO tool

Although It's not an exposure mode on its own, you can go a step further combining one of the semi-automatic modes (Priority to Aperture or Priority to Speed) or Manual together with the automatic ISO tool.

First, let me remind you what this tool is about and explain how you can set it.

Then, we'll see how you can get the most out of each of the different exposure modes.

All aboard!

How it works

At the end of section 5 I talked about the danger of using the automatic ISO of your camera without setting any limits. The problem is that depending on the camera model you use, your noise tolerance is different. That is, the ISO up to which you can shoot without noticing the noise is different: in some cameras it's 800, in others it may be 6400...

So my recommendation is that you always keep the ISO as low as possible when you're exposing. Especially if you have a low end camera (the low budget ones aimed at beginners).

If you have a mid or high-end camera, using the automatic ISO can be a very interesting option. But you have to make sure to set an ISO range according to your camera's capacities.

What range?

Easy.

The bottom is always the ISO base of your camera (ISO 100 or 200). And the top is the ISO level from which your camera generates a lot of noise and the grain is visible in the image.

Imagine that this level is 6400. In that case, the automatic ISO range you have to set in the camera is between 100 and 6400.

This keeps the noise under control.

In addition to this, the vast majority of cameras allow you to decide the minimum shutter speed. That is, you force the camera to maintain a shutter speed equal to or faster than the one you selected.

For example, if you know that to freeze a moving car you must shoot at least at 1/1000s, enter this value. So the camera, whenever possible, will use this shutter speed or a faster one (1/1250s, 1/1600s...) so that your subject is always frozen.

Once these parameters are defined, you can use this function by combining it with the Aperture Priority (A or Av), Speed Priority (S or TV) and Manual (M) exposure mode.

Let's see how taking the following parameters as a reference for this example:

- The lens has an aperture between f/2.8 and f/22.

- The automatic ISO has a range between ISO 100 (base) and ISO 1600.

- The minimum shutter speed has been set at 1/500s.

- The maximum shutter speed of the camera is 1/4000s.

How to use the Aperture Priority mode (A or Av) with the automatic ISO

We saw in section 4 that the aperture is the element that allows you to control the depth of field, that is the area of the scene is in focus on the picture.

As I explained above in this section, when I mentioned the Priority to Aperture mode (A or Av), once you choose the aperture the camera sets the shutter speed.

And now that you have set the automatic ISO, the camera is also busy setting the ISO. But an ISO restricted to the range that you have determined. In this case, and following the example, between 100 and 1600.

Imagine that you get a correct exposure thanks to an aperture of f/8, a speed of 1/500s and an ISO 100.

If you are looking to reduce your depth of field, increase the aperture (f/5.6, f/4, f/2.8 for example).

At the same time, according to the reciprocity law (section 7), if you change the aperture, the shutter speed changes as well. In this case it's increased (1/1000s, 1/2000s, 1/4000s for example).

And the ISO? It remains the same because 100 is within the reference range.

If, on the other hand, you want to increase the depth of field, reduce the aperture (f/11, f/16, f/22 for example).

Again, thanks to the reciprocity law, the shutter speed would have to change as well. In this case, the shutter speed would be slower. However, when you decide the auto ISO settings, you have told the camera that it can't use a speed slower than 1/500s. And you get the correct exposure at 1/500s.

If the camera can't slow the shutter speed, what parameter can it increase?

Exactly: the ISO.

How much? As much as the aperture has changed. And according to the example that would be 1, 2 or 3 stops: 200, 400 or 800.

| Aperture | Shutter Speed | ISO |

|---|---|---|

| f/2.8 | 1/4000s | 100 |

| f/4 | 1/2000s | 100 |

| f/5.6 | 1/1000s | 100 |

| f/8 | 1/500s | 100 |

| f/11 | 1/500s | 200 |

| f/16 | 1/500s | 400 |

| f/22 | 1/500s | 800 |

But... There's always a but, I know.

Imagine now that you have a scene somewhat darker than the previous one and the settings for a correct exposure are f/4, 1/500s and ISO 100.

You want to get a starburst effect with a light source and you decide to close the diaphragm as much as possible (f/22). As an ISO of 1600 (the maximum you have told the camera you can use) isn't enough to get a correct exposure, the camera decides to reduce the shutter speed to 1/250s. It's more important to get a correct exposure, despite the minimum shutter speed is changed.

| Aperture | Shutter Speed | ISO |

|---|---|---|

| f/2.8 | 1/1000s | 100 |

| f/4 | 1/500s | 100 |

| f/5.6 | 1/500s | 200 |

| f/8 | 1/500s | 400 |

| f/11 | 1/500s | 800 |

| f/16 | 1/500s | 1600 |

| f/22 | 1/250s | 1600 |

According to these examples, you can deduce that using the Aperture Priority mode (A or Av) combined with the automatic ISO:

- It's very unlikely that your photo will be dark (underexposed), as the camera gives more importance to the correct exposure than to the minimum shutter speed you have selected, and it can be up to 30s. Of course, from a certain shutter speed onwards you need a tripod to avoid a blurred picture.

- It's much more likely that your photo will be blown out (overexposed). Imagine you have selected a very wide aperture and the camera is already using the lowest ISO. The camera may need a shutter speed faster than the maximum speed allowed by the camera (for example 1/4000s), so the sensor will get more light than necessary. Here the solution would be either to close the diaphragm, or to use an ND filter.

How to use the Shutter Speed Priority mode (S or Tv) with the automatic ISO

As with the aperture, I explained in section 4 that you can freeze motion or show it thanks to the shutter speed.

Moreover, I told you when describing the Speed Priority mode (S or Tv) in this section that as soon as you choose the shutter speed, the camera is concerned with determining the aperture.

And now that you have set the automatic ISO, the camera is also busy setting the ISO. But an ISO restricted to the range that you have determined. In this case, and following the example, between 100 and 1600.

Imagine that you get a correct exposure thanks to an aperture of f/5.6, a shutter speed of 1/30s and an ISO of 100.

If you want to show more motion blur, slow down the shutter speed (1/15s, 1/8s, 1/4s for example).

At the same time, according to the reciprocity law (section 7), if you change the shutter speed, the aperture varies as well. In this case it's narrower, to compensate for a slower shutter speed (f/8, f/11, f/16 for example).

And the ISO? It remains the same because 100 is within the reference range.

But be careful! If you use a shutter speed slower than 1/2s the picture is overexposed. You can no longer close the diaphragm nor can you lower the ISO...

If, on the other hand, you want to freeze the motion, use a faster shutter speed (1/60s, 1/125s, 1/250s for example).

Again, thanks to the reciprocity law, the aperture would have to change as well. In this case, the aperture would be wider. However, your camera can not open the diaphragm beyond f/2.8 with a shutter speed of 1/250s. What parameter can you increase?

Exactly: the ISO.

How much? As much as the shutter speed has changed. And according to the example that would be 1 stop, or ISO 200.

| Aperture | Shutter Speed | ISO |

|---|---|---|

| f/2.8 | 1/4000s | 1600 (underexposed) |

| f/2.8 | 1/2000s | 1600 |

| f/2.8 | 1/1000s | 800 |

| f/2.8 | 1/500s | 400 |

| f/2.8 | 1/250s | 200 |

| f/2.8 | 1/125s | 100 |

| f/4 | 1/60s | 100 |

| f/5.6 | 1/30s | 100 |

| f/8 | 1/15s | 100 |

| f/11 | 1/8s | 100 |

| f/16 | 1/4s | 100 |

| f/22 | 1/2s | 100 |

| f/22 | 1s | 100 (overexposed) |

However, a shutter speed of 1/250s is not fast enough to freeze motion the way you want. That's why you decide to set it to 1/4000s, the maximum the camera allows.

And... Oh surprise! The image is underexposed because you would need an ISO of 3200 but your ISO range only allows the camera to use a maximum ISO of 1600.

According to these examples, you can deduce that using the Shutter Speed Priority mode (S or Tv) combined with the automatic ISO:

- If you need an ISO that goes beyond the top of the range you set, your photo is dark (underexposed).

- If you need a slow shutter speed your photo will be probably blown out (overexposed) because the sensor received light for too long.

How to use the Manual mode (M) with the automatic ISO

Thanks to the Manual mode (M) you are the master of the universe: you control the aperture and the shutter speed as you like.

Let's see an example to see how you can combine it with the automatic ISO.

You are in a basketball court watching a game and you want to take pictures of the players in action.

You want to have enough depth of field to capture the players in their environment. You also want to freeze the motion.

These artistic and circumstantial decisions lead you to the correct exposure settings: f/8 and 1/1000s. The camera automatically chooses ISO 1600 to get the correct exposure. It's a high ISO because, although there is artificial lighting, the light in the scene is not powerful enough to use a lower ISO.

After the first photos, you check that you can freeze the motion at this particular shutter speed.